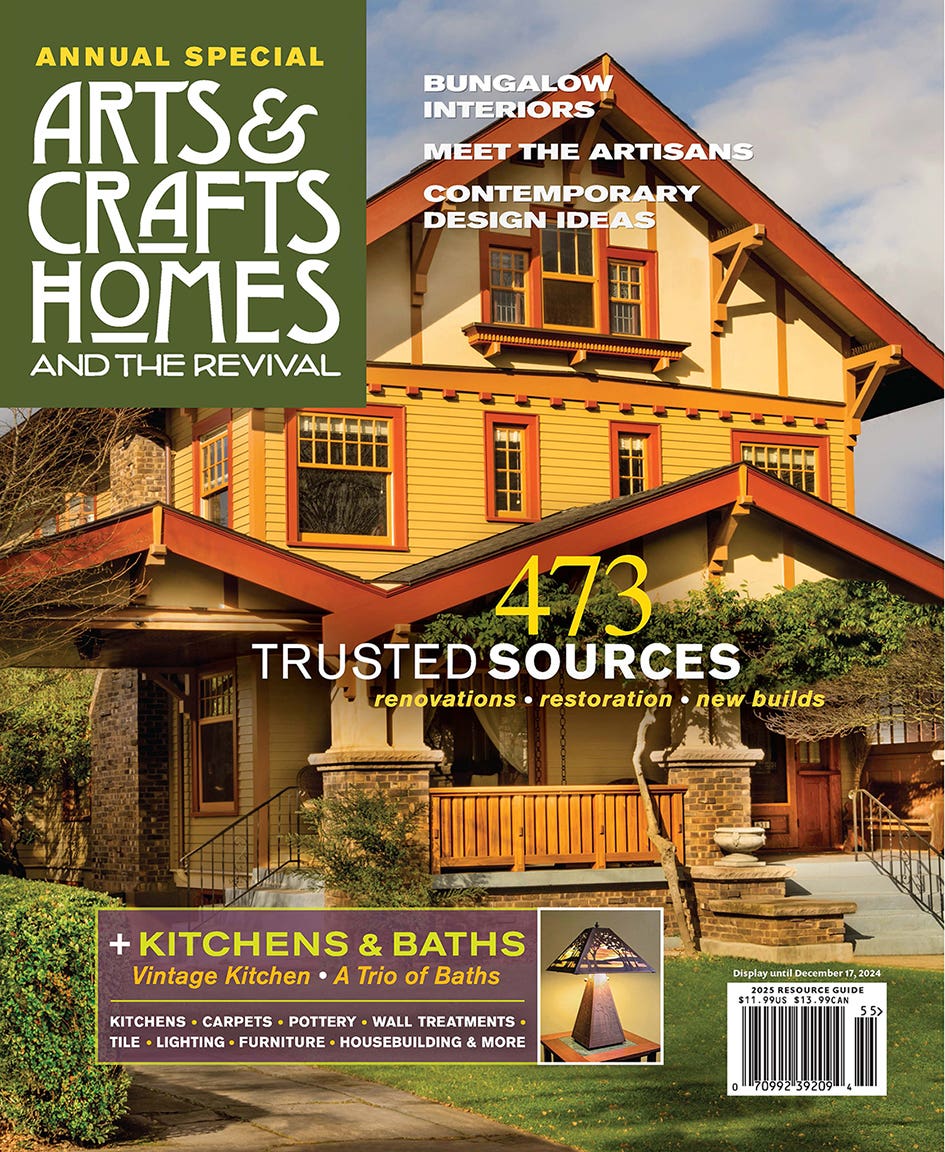

Dreaming Up a Craftsman in Portland, Oregon

A 1914 Craftsman house is restored with sensitivity.

Once upon a time, Michelle Kelly was a little girl growing up in New Zealand, where she lay awake imagining the beautiful house she would own someday. It would definitely be historic—a natural stony and woodsy place with an impressive façade. Inside it would feel big and warm and welcoming, and she would raise a family.

Michelle’s love of old houses and restoration became a theme in her life. As a teenager she pored over design magazines and books, and soon after high school began restoring and selling small homes. When she’d saved some money she moved to the United States, where so many of the beautiful homes in her books seemed to be. Michelle discovered Portland, Oregon, with its wealth of period housing stock, and in no time she was busy restoring modest rentals and bungalows. Always with a good eye for a bargain, she once traded a microwave oven for a house.

Soon she noticed a commanding Craftsman perched on a nice corner lot in northeast Portland. She would sit in her car and gaze wistfully at it from across the street. Built in 1914 for newlyweds Wilbur and Evelyn Reid (he was the son of a Portland lumber baron), the house once sat on 50 acres. It was grand even for its time, with 4,800 square feet and boasting such amenities as a ribcage shower, built-in vacuum system, an elegant stained-glass window on the landing, and even a carriage house with a car wash built into the eaves. (The Reids had honeymooned in southern California and were perhaps influenced by the work of architect brothers Greene & Greene.)

Then, in 1998, Michelle’s father passed away and left her his cherished 1924 fire-engine-red Chevrolet Tourer. Right away she thought of the Reid house and its wide porte-cochere. The house had recently come on the market, so Michelle persuaded her husband George, an avid tree climber, to give his stamp of approval by climbing 70 feet up one of the spreading copper beeches on the property. Their offer was accepted.

Many original features were intact, from the exterior’s bracketed eaves and broad front porch to the quarter-sawn oak beams and mahogany woodwork inside, which had never been painted. Yet the place had had little attention for 40 years, and the wet climate had taken its toll. Most of the more than 400 rafter ends suffered from rot. Downstairs walls were a fleshy pink, and very shiny vinyl wallpaper covered stairway walls like a cellophane candy wrapper. The kitchen was a warren of small rooms with black and yellow linoleum countertops ruined by decades of cooking grease. All the systems needed significant updating or complete replacement.

The family started outside. Rafters were repaired with Abatron products and sealed with copper caps. Masonry was repointed. Wood shingles were sanded and stained, returned to their silvery grey color with an application of Sherwin Williams’ “Gray Shingle”; trim was painted their “Chocolate Brown.” Windows with old glass were carefully preserved, sashes rehung with new ropes. Eleven original screen doors were still in use, so they were stripped and resealed with clear varnish to show off the fir. A century-old Chinese wisteria was invigorated and trained to follow the route of the original vines on three sides of the house.

Michelle and George decided to take their time in side, patiently learning the rhythms of the house first: how light travels throughout the day, how the family used rooms, where it was drafty and what all the little noises meant. Thus they found the best location for the master bedroom (main floor, next to the period bathroom). They found that yes, they did really use the five doors off the kitchen, that summer afternoons were best in the shade of the front porch. After two years they knew the house well enough to make prudent and period-appropriate improvements.

The existing kitchen was uncomfortable—three tiny rooms and five doorways. Michelle admits this project was difficult: trying to keep the integrity of the early 20th-century plan while making the space usable. Viewed from the dining room (above), the new kitchen carries through colors and materials found in the rest of the house. Yet it has a clean and modern utility (opposite). All five doors are still here, and the pantry has been converted into a bar. Period-inspired, custom-made fir cabinets hang over mahogany countertops and plain subway-tile backsplashes. The flooring is walnut. A built-in banquette by the window provides dining space.

Systems updates finished, Michelle made the lucky discovery of two small, double-hung side windows stored in the house, which she added one to each side of the stairway’s stained-glass panel, coaxing in more light on overcast days. George cleaned and varnished all of the mahogany and oak woodwork. Living-room walls got a soft Liberty wallpaper that continues the warm tones of the woodwork. Michelle took the dining room’s Victorian chandelier as a cue to paper the room in a darkly exotic Chinese landscape paper.

Upstairs, the couple had replacement tile installed in the handsome original bathroom, which retains its porcelain tub and sink and its tiled laundry chute. A tiny room under the eaves became a cozy guest room with a romantic Art Nouveau wallpaper from Switzerland and a simple painted iron bed.

Brian D. Coleman, M.D., is the West Coast editor for Arts & Crafts Homes and Old House Journal magazines, our foremost scout and stylist, and has authored over 20 books on home design.