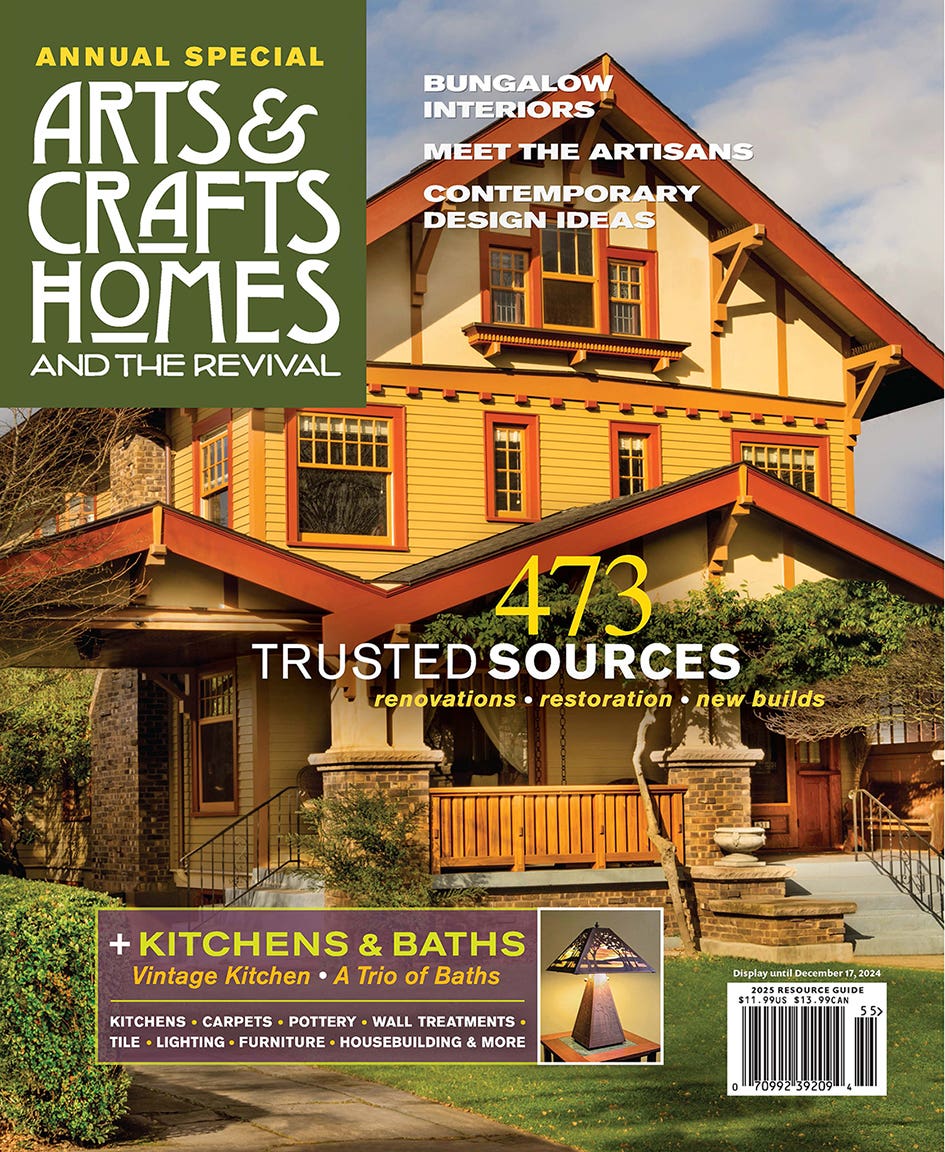

House Styles: The Craftsman Bungalow

The history and style of the heyday bungalow with its exotic, Anglo–Indian associations and artistic naturalism.

A bungalow nestles into its site, low and spreading. It was inevitable that the form would be embraced by tastemakers and builders of the Arts & Crafts movement. The architects Greene and Greene in California called their millionaires’ chalets bungalows. Gustav Stickley sang their praises in this magazine The Craftsman. Dozens of plan books between 1909 and 1925 promoted “artistic bungalows.” Only later, with the ascendancy of a middle-class Colonial Revival, did Arts & Crafts ideals lose favor; eventually, “bungalow” become a derogatory label.

The bungalow as a house form has close ties to the Arts & Crafts movement—and an even stronger affinity today, as thousands of bungalows, some quite modest, are snatched up to be interpreted in a manner that’s often beyond the tastes and budgets of the original owners.

• • • •

Hallmarks of the Arts & Crafts Bungalow

Illustrations by Rob Leanna

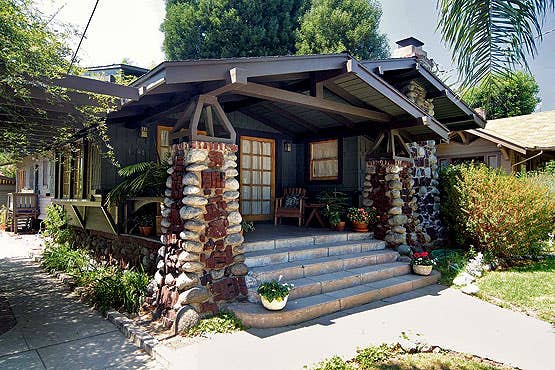

INDIGENOUS MATERIALS

An artistic use of such materials as river rock, clinker brick, quarried stone, shingles, and stucco is common.

ARTISTIC NATURALISM

Most bungalows are low and spreading, not more than a story-and-a-half tall, with porches, sun porches, pergolas and patios tying them to the outdoors. The A&C bungalow follows an informal aesthetic; it is a house without strong allusions to formal English or classical precedents.

EMPHASIS ON STRUCTURE

Look for artistic exaggeration in columns, posts, eaves brackets, lintels, and rafters. Inside, too, you’ll find ceiling beams, chunky window trim, and wide paneled doors. Horizontal elements are stressed.

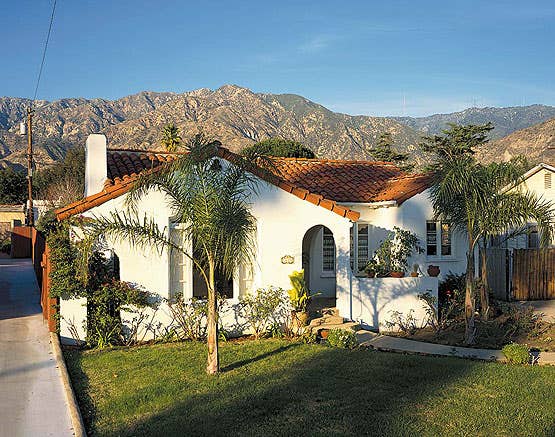

EXOTIC INFLUENCES

These appeared in builders’ houses and the pages of style books and magazines: stick ornament in the manner of Swiss Chalets; Spanish or Moorish arches and tilework; and orientalism, especially Japanesque.

• • • •

Bungalow Variants

Photos by Douglas Keister

Period bungalows can be quite plain little houses. Some nod to other styles including English Tudor, Prairie School, and, anachronistically, Colonial.

• • • •

Inside the Bungalow

The typical bungalow interior, at least as it was presented in the house books of the period, is easy to recognize. Basically, the bungalow interior was a Craftsman interior.

In a complete departure from Victorian interior decoration, bungalow writers frowned on the display of wealth and costly collectibles. Rather than buying objects of obvious or ascribed value, the homeowner was told to look for simplicity and craftsmanship: “a luxury of taste substituting for a luxury of cost.”

Keep in mind that both Greene and Greene’s Gamble House in Pasadena and a three-room vacation shack without plumbing were called bungalows. And they both affected what the typical year-round bungalow would look like. The finest examples of Arts & Crafts handiwork found a place in the bungalow, as did rustic furniture.

Walls were often wood-paneled to chair-rail or plate-rail height. Burlap in soft earth tones was suggested for the wall area above, or used in wood-battened panels where paneling was absent. Landscape friezes and abstract stenciling above a plate rail were often pictured. Dulled, grayed shades and earth tones, even pastels, were preferred to strong colors. Plaster with sand in the finish coast was suggested. Woodwork could be golden oak or oak brown-stained to simulate old English woodwork, or stained dull black or bronze green. Painted softwood was also becoming popular, especially for bedroom, with white enamel common before 1910 and stronger color gaining popularity during the ’20s.

It became almost an obsession with bungalow builders to see how many amenities could be crammed into the least amount of space. By 1920, the bungalow had more space-saving built-ins than a yacht: Murphy wall beds, ironing boards in cupboards, built-in mailboxes, telephone nooks.

Writers advocated the “harmonious use” of furnishings small and few. Oak woodwork demanded oak furniture, supplemented with reed, rattan, wicker, or willow in natural, gray, or pastels. Mahogany pieces were thought best against a backdrop of woodwork painted white. (Bright white was used most often for bathroom trim; “white” could also signify cream, yellow, ivory, light coffee, or pale gray.) A large table with a reading lamp was the centerpiece of the living room in these days before TV.

Restraint was the universal cry of good taste. Clutter was out—“clutter” being a relative term. Pottery, Indian baskets, Chinese and Japanese wares, vases, and Arts & Crafts hangings were suggested to satisfy the collector instinct. More affluent households might display Rookwood pottery, small Tiffany pieces, hammered copper bowls, and decorative items from Liberty and Co. A watercolor landscape or two, executed by the amateur painter of the family, was the ultimate Arts & Crafts expression for the home.

Books recommended by the editors for bungalow owners

Do a search at amazon.com and you’ll see there are dozens of books about bungalows and the American Arts & Crafts movement. Some of the now-classics are out of print but you can always find a used copy. Here is a basic library for owners of bungalows old and new:

• The Bungalow: America’s Arts & Crafts Home by Paul Duchscherer; Penguin Studio 1995

• Inside the Bungalow: America’s Arts & Crafts Interior by Paul Duchscherer; Penguin Studio 1997

• Outside the Bungalow, America’s Arts and Crafts Garden by Paul Duchscherer, photos by Douglas Keister; Penguin 1999

• Bungalow Kitchens by Jane Powell, photos by Linda Svendsen; Gibbs Smith 2000

• Bungalow Bathrooms by Jane Powell, photos by Linda Svendsen; Gibbs Smith 2001

• Bungalow: The Ultimate Arts and Crafts Home by Jane Powell, photos by Linda Svendsen; Gibbs Smith 2004

• Bungalow Details: Exterior by Jane Powell, photos by Linda Svendsen; Gibbs Smith 2005

• Bungalow Details: Interior by Jane Powell, photos by Linda Svendsen; Gibbs Smith 2006

• Bungalow Nation by Diane Maddex and Alexander Vertikoff; Abrams 2003

• American Bungalow Style by Robert Winter; Simon & Schuster 1996

• Bungalow Colors: Exteriors by Robert Schweitzer; Gibbs Smith 2002

More on decorating and furnishing your Bungalow:

• The Beautiful Necessity: Decorating with Arts & Crafts by Bruce Smith and Yoshiko Yamamoto; Gibbs Smith 1996 and 2004

• American Arts & Crafts Textiles by Dianne Ayres et als; Abrams 2002

• Arts & Crafts Textiles by Ann Wallace; Gibbs Smith 1999

• Arts and Crafts Furniture by Kevin P. Rodel and Jonathan Binzen, Taunton Press 2004

• Grove Park Inn Arts & Crafts Furniture by Bruce Johnson; Popular Woodworking Books 2009

• Craftsman Style by Robert Winter; Simon & Schuster 2004

• Gustav Stickley by David Cathers; Phaidon 2003

To see Prairie School domestic interiors:

• Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie Houses by Alan Hess et al; Rizzoli 2006

• Frank Lloyd Wright’s Interiors by Thomas A. Heinz; Gramercy Books

• Frank Lloyd Wright: The Houses by Alan Hess et al; Rizzoli 2005 [note : important book is oversized and heavy]

• Purcell & Elmslie, Prairie Progressive by David Gebhard; Gibbs Smith 2006

Bungalows newly built or renovated:

• Bungalow Plans by Gladu and Gladu; Gibbs Smith 2002

• Small Bungalows by Christian Gladu and Ross Chandler; Gibbs Smith 2007

• The New Bungalow by Bialecki and Gladu; Gibbs Smith 2001

• The New Bungalow Kitchen by Peter Labau; Taunton Press 2007

• Bungalow Style: Creating Classic Interiors in Your Arts & Crafts Home by Treena Crochet; Taunton Press 2004

• Updating Classic America: Bungalows, Design Ideas for Renovating…and Building New by M. Caren Connolly and Louis Wasserman; Taunton Press 2002

Scholarly histories of Bungalow architecture:

• The Bungalow by Anthony D. King; Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1984

• The American Bungalow by Clay Lancaster; Abbeville Press 1985

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.