The Language of Arts & Crafts

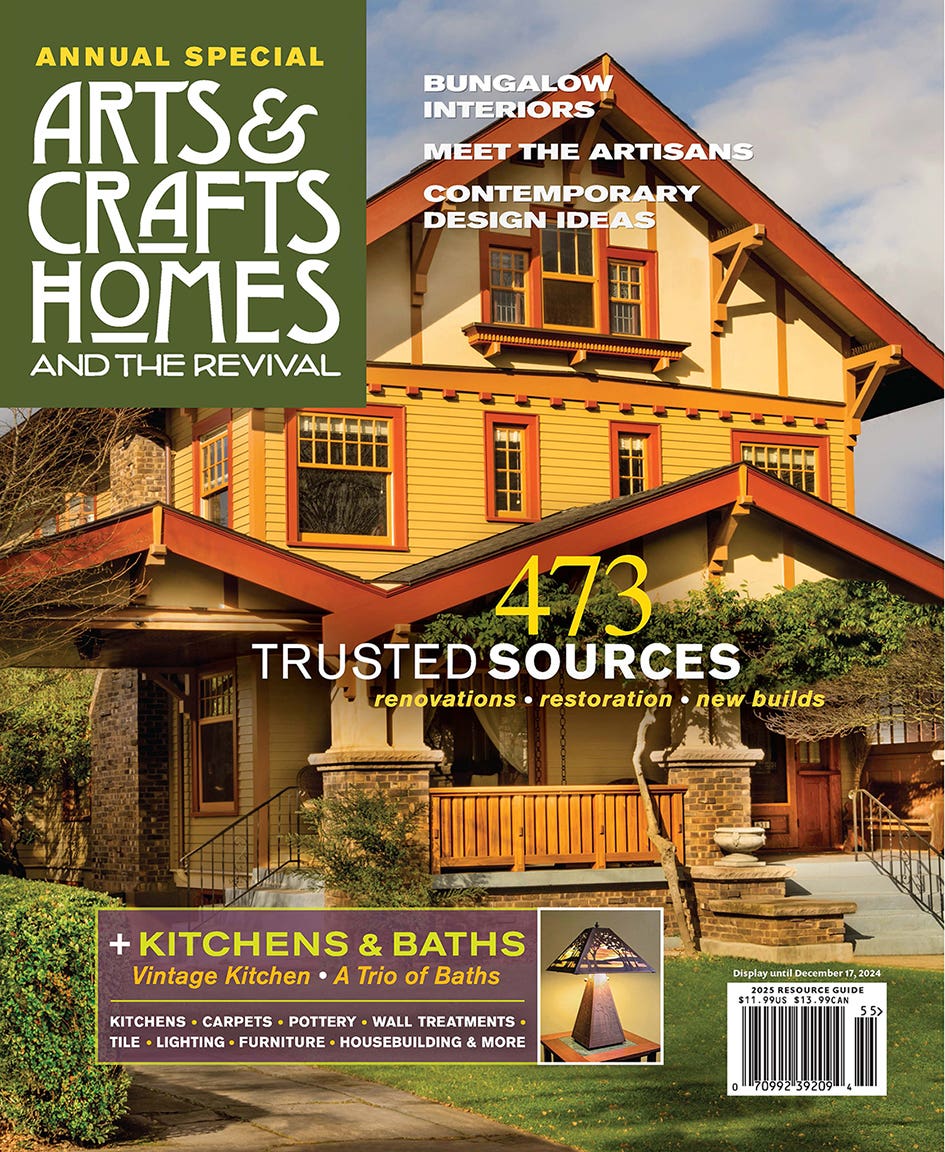

English-leaning outside with an American Arts & Crafts interior, this stunning new home has simple massing punctuated by a two-story window bay.

Before they moved to Minnesota, this family had lived in one old house—in San Francisco—and they liked the idea of collaborating with an architect to build a “new old house.” To oversee its design, they chose Joseph Metzler of SALA Architects in Minneapolis. “Joe asked the questions, and we gave answers,” Elizabeth says. She and her husband, Ian, always had been drawn to houses of the Arts & Crafts period. They especially liked the landmark Plummer House in Rochester, Minnesota, a house in the English Arts & Crafts style, which had belonged to one of the original partners of the Mayo Clinic. “We hoped our (new) house would look like it might have been built for or by one of his children,” Elizabeth says.

Metzler collaborated closely with architect Steven Buetow, formerly at SALA. The house borders a historic district, and the old houses inspired the general approach. The garage is discreetly tucked under the house in the rear slope. The exterior looks to the work of Voysey, Lutyens, and other English Arts & Crafts designers, Metzler explains. The interior, on the other hand, is more American Arts & Crafts.

“Still, I don’t feel this design is either a homage or an interpretation,” Metzler says. “I see our design process in the same light as a modern-day craftsman creating according to the ideas and tenets of the Arts & Crafts movement.”

A full-height glass bay dominates the exterior. Leather chairs furnish a well-lit reading room downstairs, which can be closed off by French doors fitted with art glass. A book-lined balcony overlooks the main space.

Casements and double-hung windows by Marvin are virtually all custom sized, allowing the designers to keep lights the same size everywhere. “It almost looks like individual glass panes all were manufactured the same size, and then windows were handmade to accommodate the number of lights needed,” Metzler explains. “The result is very different from what you get in the common practice of using standard-size windows, where the proportions of individual lights vary.”

Inside the bay, the stunning nine-light chandelier was a custom collaboration between metalworker and glass artist. (Shane Jost of Mountains Edge Copper Art did the copper- and metalwork. The art-glass lanterns came from David Haight of the Rubaiyat Studio.) The fixture hung in the owners’ previous home; they dismantled and crated it for shipping. The library was designed around its dimensions.

Metzler designed the art glass, incorporating a motif supplied by the homeowners, which ties Elizabeth’s Chinese heritage to her husband’s affection for the Mackintosh rose. “The rose is also a reference to one of my husband’s favorite hymns: ‘Lo, how a rose ere blooming,’” Elizabeth explains.

Seen in art glass in the buffet and French doors, the trefoil (suggesting a flower or rose) is based on Chinese lattice designs shown in a book by Daniel Sheets Dye. It is abstracted as a hexagonal lattice in such custom tile features as the fireplace surround. The hexagonal repeat recalls designs that would have been common in Chengdu, in the Szechuan region of China, around the time that Elizabeth’s father’s family lived there (ca. 1900). Breaking the hexagon in half was a practical suggestion made by Roger Mayland of North Prairie Tileworks.

Embracing the idea of a “new old house,” the owners were able to accept a more contemporary feel in the kitchen, given their “story” that this once would have been exterior space, later enclosed and repurposed—hence the stuccoed walls and exposed brick arch, the serviceable beadboard ceiling and floor tiles. The room is divided into prep, cooking, wash-up, and baking zones, with storage for each purpose nearby.

The couple has begun to collect vintage pottery. But “our take on this being a Craftsman house is that we should support and encourage contemporary craftsmen,” says Elizabeth.

Also in keeping with the Craftsman tradition, the house was built with a reliance on local sources and talent. “It pleases us that the craftsmen and tradesmen involved can reference our house as a showcase of their skills.”

Revival Baths

Recalling the best bathrooms of the early 20th century, these period-inspired rooms incorporate custom Arts & Crafts-style details. Both the master and boys’ bathrooms have built-in cabinets conceived of as tall, freestanding dressers, a refinement of bungalow-era millwork. Sloped sides and the base treatment give them the look of Arts & Crafts furniture. Reflecting the “sanitary” bathrooms of the era, millwork has a glossy, white-painted finish. Fixtures and lighting also repeat the look of bungalow-era bathrooms.

As is so often the case in quirky old houses, a limitation led to a handsome design: The arch over the sinks was required due to low headroom at this end of the room under the slope of the roof.

Oak and custom tile in a deep color provide a more “furnished”look in the downstairs powder room. Tile is by North Prairie Tileworks. (Subway tiles on walls have a custom glaze, Thayer 8. The floor is glazed with #19 Blue Green with the listello, or liner, in #190 Woo Blue. All are mid-range glazes from the company’s electric kilns.) Even here, though, the white plumbing fixtures remain a classic. “I particularly like that the white fixtures stand out in the warm-toned room; there’s no attempt to hide its function,” says Metzler.

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.