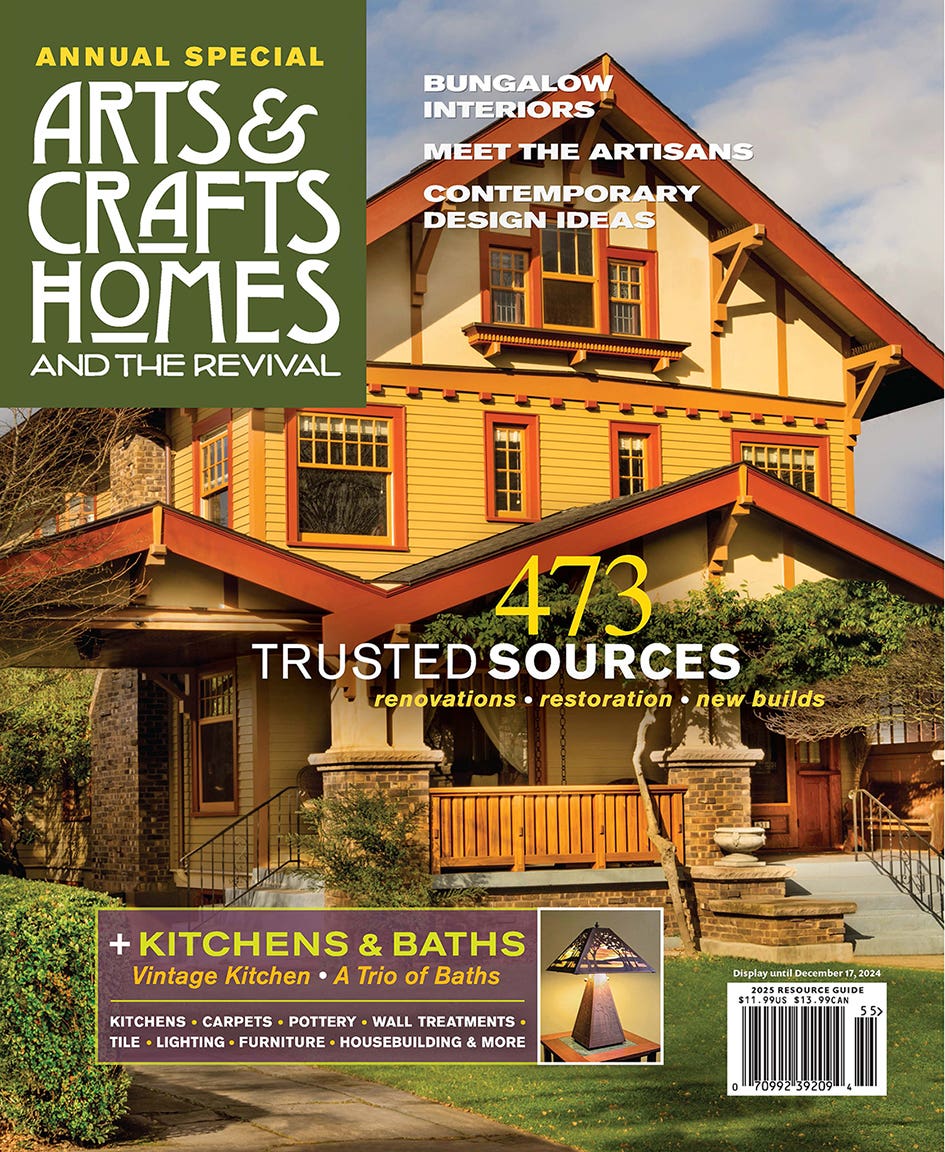

The Bungalow: A Short History

How the darling house style of the first quarter of the 20th century lost its cachet, and why the American Bungalow has come back stronger than ever as part of the Arts & Crafts Revival.

America had a long love affair with the Bungalow—for two decades a torrid one—and the old flame has been rekindled. This is the story of how an exotic Anglo–Indian word came to mean a new American house style. Bungalows came from India, so say popular accounts, but it wasn’t that simple. The word (or variations of it) existed for hundreds of years before any bungalows showed up here. “Bunguloues,” temporary and quickly erected shelters, were referred to by an Englishman in India in 1659; we find “bangla,” “bungales,” and “banggolos” before the English spelling “bungalow” superseded others by 1820. [See Anthony D. King in The Bungalow, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1984]

The English in India were describing houses built for them by native labor: long, low buildings with wide verandahs and deeply overhanging eaves. Broad roofs, first of thatch and later fireproof tile, enclosed an insulating air space against tropical heat. Then, around 1870, builders of newly fashionable English seacoast vacation houses referred to them as “bungalows,” giving them an exotic, rough-and-ready image.

The bungalow showed up in America in the 1880s, scattered here and there and especially in New England. But it was its development in Southern California that paved the way for its new role as a year-round house, and tuned it into the most popular house style American had ever known.

The California Bungalow

The climate was perfect for a rambling “natural” house with porches and patios, of course, but there were sociological reasons, too, for the American Bungalow’s birth in California. Los Angeles and upscale Pasadena, an 1890s resort town, were growing fast. By 1930, Los Angeles would have more single-family dwellings that any comparable city, with 94% of its families living in single-family homes! An essential part of this mass suburbanization was “an innovative, small, single-family, simple but artistic dwelling; inexpensive, easily built, yet at the same time attractive to the new middle-class buyer.” Enter the California Bungalow, a term that was in use by 1905 if not before.

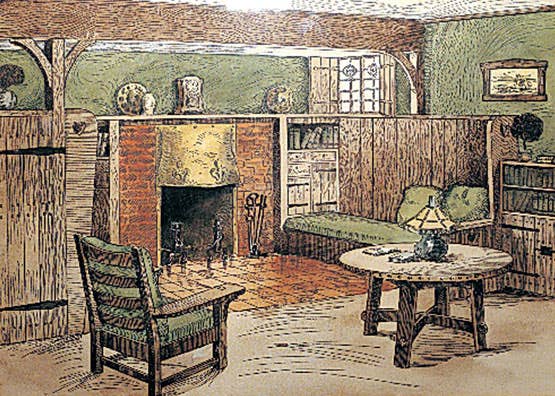

The California Bungalow was soon a well-defined new style. Its sympathetic relationship with its site was paramount. The Bungalow hugged the ground. Indoors and outdoors intermingled in terraces, verandahs, screen porches, patios, courts, pergolas and trellises. Natural materials—in California, boulders and wood—made up the exterior and went inside. The idea took off—how many house styles have songs written about them? (More about that below.)

The greatest artists of the Bungalow Style were brothers Charles and Henry Greene, architects who shed their neo-Colonial and Queen Anne motifs to explore the possibilities of a true craftsman-built home. This was after a trip to England by Charles in 1901; he brought back Arts & Crafts ideals probably ten years before that movement would have reached the West Coast of the United States. They took an artistic leap, attempting to synthesize the best of many worlds into a new California vernacular: the adobe and Mission forms of the region, the rugged Shingle Style of Richardson in the Northeast, the Italian and Japanese architecture the brothers had studied.

The Greenes picked the chalet, a folk carpenter’s dream, as their base, looking not for a touch here and a touch there but instead the essence of the chalet: an uncomplicated and massive roof, exposed structure. They called the houses “bungalows,” not inventing bungalows but transforming them from a lower form of temporary architecture.

Prairie Style and Craftsman Influence

Meanwhile, 2000 miles away, the Prairie Style was being developed by a group of innovative young architects that would soon be known as the Chicago School. Frank Lloyd Wright would become the most famous, but he was by no means a lone innovator. The Chicago architects were also building one-story houses, playing off the horizontal lines of the Midwestern prairie. The designs were not bungalows in any sense of the Indian root of the word.

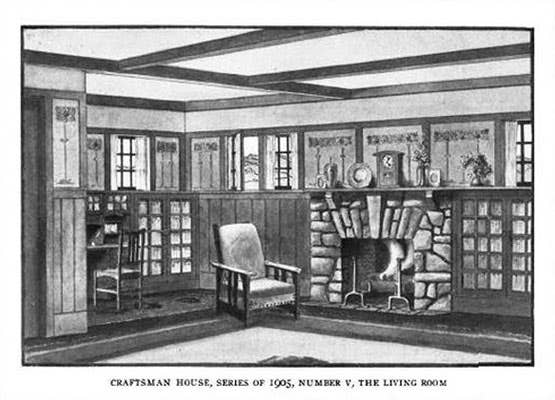

But, like Greene & Greene, the Chicago architects were influenced by the Arts & Crafts movement, and their simple (by Victorian standards) woody interiors were similar to those of the West Coast Bungalows. Greene & Greene and Frank Lloyd Wright were regularly published in Gustav Stickley’s The Craftsman magazine, the mouthpiece of the American Arts & Crafts movement.

The most persuasive voice for reform in residential architecture between 1901 and 1916, The Craftsman was an important factor in the popular development of the American Bungalow. Ladies Home Journal was also a great Bungalow backer. But directly or indirectly, it was Stickley’s appreciation of the Bungalow as an embodiment of Craftsman architectural ideals that gave it its wider appeal.

Stickley’s message had three major principles: simplicity, harmony with nature, and the promotion of craftsmanship. Greene & Greene themselves might have chanted the words. Their Bungalows, and others in Southern California, were an incarnation of all three principles. The same could be said of Prairie School houses.

Stickley became an ardent Bungalow proponent from 1903 onwards, writing such things as [the Bungalow is] “a house reduced to its simplest form where life can be carried on with the greatest amount of freedom; it never fails to harmonize with its surroundings...” etc. ,etc. Stickley’s descriptive, profoundly influential prose equated the Bungalow Style with the essence of Arts & Crafts philosophy.

Other house writers soon understood the relationship between Craftsman houses and the Bungalow. In Bungalows (1911), Henry Saylor refers to furniture in “the so-called Craftsman style,” later suggesting that “nothing seems so thoroughly at home in the bungalow living-room as the sturdy craftsman furniture of brown oak...” In many people’s minds, both tastemakers’ and new homeowners’, Craftsman and Bungalow were so closely allied as to be the same.

The Builder’s Bungalow

The bungalow is usually thought of as a small house. Yet at first, in America at least, the style had nothing to do with size. True Southern California Bungalows at the turn of the century were quite large, with rambling floor plans, extensive grounds, three or five or seven bedrooms, living rooms of 20 x 25 feet, and multiple porches. All of this was about to change.

During this period, home ownership was becoming a realizable American dream for a middle class whose numbers were exploding. Speculative building and patternbook companies were booming. A need existed for small and simple house that would look good even if plainly built and furnished. The word “bungalow” had been happily adopted, even then without a clear definition, by a public who had read all about bungalows in magazines. It was a type of house that didn’t need much hype or hoopla; somehow, it was, and still is, intrinsically appealing. Perhaps a bit radical (bedrooms on the parlor floor?!), it was nevertheless embraced. Any anyway, its more radical features could be softened by builders who designed for mass appeal.

First to go was its strict definition as a one-story house. At first, builders simply put dormers in the steep roof, allowing room, light, and ventilation for attic bedrooms; such houses they called “semi-Bungalows.” Inevitably, more compromise was made; the region and the clientele had changed. Early Bungalows were low-lying, rather rough structures buried in the woods or on a hillside or among the boulders at the seashore. But later builders were creating suburbia. If it had more than just a bedroom or two, a one-story house was prohibitively expensive; a bungalow has more foundation, exposed wall surface, and roof in proportion to the space enclosed than does a two-story house.

Even back in the 1910s and 1920s, architecture writers and critics were aghast at the “misuse” and overuse of the word. Charles White Jr., in his The Bungalow Book of 1923, tells us only that the current definition is “a curious example of how we Americans overwork a word that is euphonious and the meaning of which, because of the word’s comparatively recent assimilation into the language, is somewhat uncertain.” However, after briefly and pretty accurately recounting the evolution of the true Bungalow, he goes on to show examples that make it clear he’s going with the flow: He considers any country or suburban home that is informal and picturesque to be a bungalow. These same writers continued to wrap Prairie houses in the Bungalow blanket: In White’s book, an early residential design by Frank Lloyd Wright is captioned “A Bungalow of the Midwestern Type.”

What really happened during the bungalow building boom is that the bungalow was no longer a pure structural type, but a broader house style. A house could be built “along Bungalow lines.” Some historians call these houses “bungaloid,” but that’s an unfortunate and unfair word. We cannot look back now and say that literally millions of homes, many of them picturesque, well built, and stylish, were aberrations. Instead, let’s accept the fact that the definition of bungalow broadened over time. This was “the bungalow period” of residential architecture.

The Beginning of the End

Anyway, as early as 1908 the word with the fashionable cachet was being used for many small houses that had only the vaguest bungalow allusions. In the 1920–21 Aladdin Homes catalog, more than half the models were, stylistically and in name, recognizable Bungalows. But the inevitable change in popular taste was already apparent: The same catalog also included an unbound supplement entitled “Colonial Bungalows,” which were nothing more than tiny, inexpensive houses with Colonial motifs.

By 1928, the fat Home Builder’s Catalog was full of Colonial Revivals, unremarkable “suburban homes,” and houses with vaguely English lines. There’s also an odd hybrid labeled “a duplex bungalow”...even the word’s previously respected definition as a single-family (if not single-story) home had been thrown aside. The scattered use of the word “bungalow” in the catalog was more a case of the copywriter searching for a synonym than any reference to style.

Ironically, the 1920s was the boom period for bungalow building even as its decline began. Instead of “simple, rustic, natural, charming,” the bungalow glut was beginning to change the connotation of the word to “cheap, small, and vulgar.” You knew the bungalow bust was coming when Woodrow Wilson described President Warren Harding as “bungalow minded” and meant that he had a limited thinking capacity. It was unprecedented suburban growth, no longer bungalove, that kept the bungalow strong through the late 920s.

After the Second World War, as we all know, the word was revived to mean a cheap vacation house by the seashore or lake—oddly enough, not so terribly far from its first use in England in the early 19th century.

It’s that cruel last association that the Bungalow has had to live down.

• • • •

BungaLove

How many house styles have had poems and songs written about them? Bungalyrics abound; one historian claims to know of 22 songs about the beloved Bungalow. Sometimes the melodious word itself provided inspiration, as in this verse first published in no less a mainstream magazine than Good Housekeeping in 1909.

There’s a jingle in the jungle,

‘Neath the juniper and pine,

They are mangling the tangle

Of the underbrush and vine,

And my blood is all a-tingle

At the sound of blow on blow,

As I count each single shingle

On my bosky bungalow.

There’s a jingle in the jungle,

I am counting every nail,

And my mind is bungaloaded,

Bungaloping down a trail;

And I dream of every ingle

Where I angle at my ease,

Naught to set my nerves a-jingle,

I may bungle all I please.

For I oft get bungalonely

In the mingled human drove,

And I long for bungaloafing,

In some bungalotus grove,

In a cooling bung’location

Where no troubling trails intrude,

‘Neath some bungalowly rooftree

In east bungalongitude.

Oh, I think with bungaloathing

Of the strangling social swim,

Where they wrangle after bangles

Or for some new-fangled whim;

And I know by bungalogic

That is all my bungalown

That a little bungalotion

Mendeth every mortal moan!

Oh, a man that’s bungalonging

For the dingle and the loam

Is a very bungalobster

If he dangles on at home.

Catch the bungalocomotive;

If you cannot face the fee,

Why, a bungaloan’ll do it —

You can borrow it of me!

—Burgess Johnson, 1909

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.