The Word “Craftsman” and other Arts & Crafts-Era House Styles

The word “Craftsman” is often used in reference to American Arts & Crafts style. A Craftsman Home, though, is something more defined.

“Craftsman” is a dwelling built according to plans published by Gustav Stickley in his magazine and reprint books. (Anything else is more accurately called Craftsman-style, or better yet, Arts & Crafts.) About 240 plans were published between 1904 and 1916.

These houses were embraced by the top of the plan book market; the cost to build was well above average and customizing was prevalent. (Some elements, however, such as hand-wrought copper hoods and extensive hardwood built-ins, rarely made it into construction budgets.) Craftsman Homes are diverse; fewer than half could be called Bungalow style. That’s true of Arts & Crafts-era houses in general. Only with hindsight, it seems, can we connect the many facets of the Arts & Crafts movement. Its emphasis on philosophical underpinnings, indigenous materials, and the vernacular meant that various regions and traditions would find different expressions.

Arts & Crafts was embraced by architects and tastemakers, but also by planbook publishers and builders. Elements of style and size vary widely in these houses. Except in woodsy locations, wood doesn’t necessarily predominate. Stone, cement, adobe, and tile are common, and brick appears where the material has local precedent.

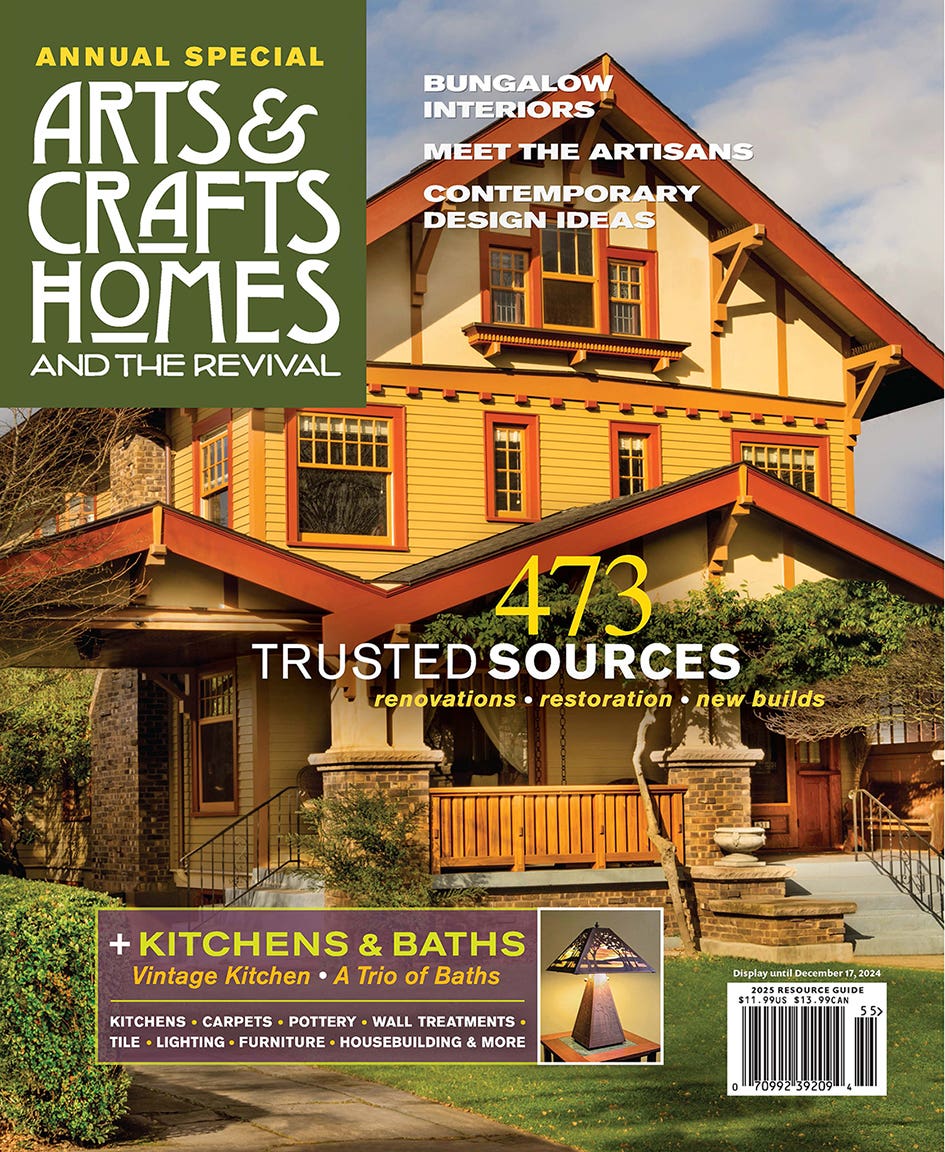

Some typical regional variations of houses built during the Arts & Crafts era are artistic Bungalows, Tudoresque and Prairie School houses, and the adaptable Foursquare.

Like the Elizabethan Revival example on Long Island, New York, some houses were very English. Steep roofs, oriel windows and diamond lights, decorative half-timbering—motifs familiar from the Victorian Queen Anne style—found their way into Arts & Crafts homes, especially on the East Coast. Arts & Crafts Tudor is a sub-style of its own.

The West Coast saw building booms during the bungalow era—and that house type was perfect for mild climates and healthy outdoor living. Here the Arts & Crafts Bungalow flourished, and was rendered in every sub-style, looking here like a hacienda, there a pagoda. Japanese influence was strong.

From Milwaukee to Kansas City, Prairie School-influenced houses were built by architects and spec builders alike. Though they had a strong regional character and a modern look, these houses, too, were part of the Arts & Crafts sensibility. Stickley published early examples in his magazine.

The so-called Chicago Bungalow is an anomaly—it’s made of brick, and rather enclosed as urban houses will be. Tracts of these very recognizable middle-class dwellings can be found in many Chicago suburbs. They typically incorporated Prairie School motifs such as geometric art glass in banded windows, low-walled stoops, and stylized façade ornaments.

The American Foursquare showed up nationwide. It may have been designed with Prairie School influence, or, later, with Colonial Revival details. Between 1900 and 1915 or so, the Foursquare was often made “artistic” with elements borrowed from the Bungalow: battered porch piers shingled or made of stone, decorative rafter tails under deep eaves.

What Arts & Crafts houses have in common is a merger of indoors and out (porches, pergolas, overhanging eaves), the artful use of natural materials (stone chimneys, clinker bricks), and an exaggerated show of structure (battered column piers, eaves brackets).

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.