Universal Design in the Arts & Crafts Spirit

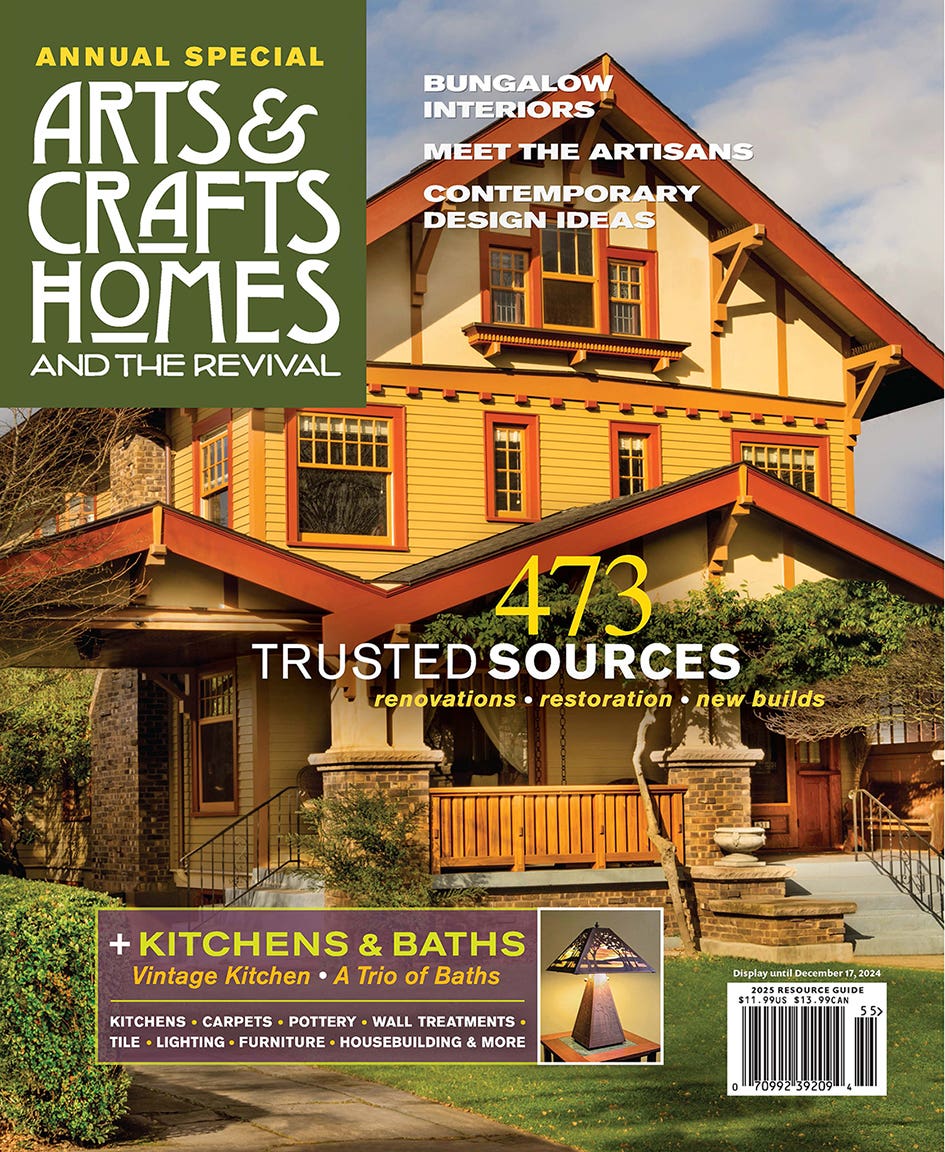

A passion for period design plus issues of mobility created this new home in St. Paul.

"Our last one was a 1912 American Foursquare,” says Mary Griffin, who imagined this house along with her husband, Raymond Dietman, and architect Jeremiah Battles. Built on an open lot in the St. Anthony Park neighborhood of St. Paul, Minnesota, it immediately fit in. “We wanted the beautiful things about our old house transferred to an accessible house,” Mary explains, “so the new house was designed to feel like the old one. Our architect and contractor understood completely, and included the mouldings, cabinets, and details found a century ago.”

Ray wears a leg brace and sometimes uses crutches for more stability; too many falls made the couple realize they needed a place where he could avoid stairs and with an attached garage—a house that would suit the couple for years to come. (The basement in the new house can be turned into a caregiver apartment, for example.) “We could have moved half a mile north and found a lovely one-level rambler, but we wanted to stay where we know people on every block,” Mary says.

“As a teenager, I lived in England and went to a boarding school that had been remodeled by Lutyens,” she says. “That became my reference point for the architecture I love—I admit to being an Anglophile. Fortunately, Ray shares my taste.” The couple appreciated the old Foursquare’s Arts & Crafts details, the oak woodwork, beveled glass and built-ins, art-glass doors in the dining-room buffet.

Incorporating architectural salvage in the new building contributed to its always-been-here feeling. During the design process, Mary found vintage lighting fixtures, a Tudor fireplace surround, and even beveled glass for windows and doors. “I started with one big piano window,” she says, referring to an ornamental horizontal window under which their upright piano now sits. “Jeremiah said that if I stuck to clear beveled glass, avoiding stained- and frosted-glass patterns, the windows would seem to match.” Five interior (room to room) windows are fitted with salvage. The salvaged front door is a simpler version of an elaborate beveled-glass door Mary has admired on Summit Avenue in St. Paul: “At night, it glitters like a ballroom.”

The restoration company Lightworks in Minneapolis made kitchen pendants and sconces to match a 1912 Sheffield fixture that Mary had found for her dining room. And “I have 13 antique glass shades collected over the years, brought over from our old house—they’re very graceful and I like the way they diffuse light.” Mary has also made simple curtains out of vintage linens. With a long list of needs and wants, Mary Griffin was very involved in the design process. She’d been eyeing the building lot for a decade, dreaming up houses in her head. Needs were obvious. Wants included bedrooms with cross-ventilation, a den for Ray right by the kitchen, and a coffeepot in the master bathroom. She wanted the basement to open to a patio, and “an upstairs hall that had windows and a place to do something instead of just pass through.”(Theirs has bookshelves and a daybed, and leads to an upstairs balcony.)

The couple’s restoration contractor was Ben Quie, who agreed to build the new house. Ben suggested the young, talented architect Jeremiah Battles, just starting his own firm, Acacia Architects. As it turned out, “I never called anyone else,” Mary says; “…once we started talking to him, Jeremiah clearly understood, he was perfect for this job.

“God bless him, he involved me in every decision, which I really enjoyed, but he didn’t let me screw up his beautiful design,” Mary laughs. The architect and contractor liked working together. Mary also called in colorist Susan Moore, who chose the palette and also suggested the recessed sink in the powder room.

The house takes maximum advantage of a southern exposure, staying light and warm in winter, while roof overhangs shield the summer sun. Ample windows keep warm, rich colors in rooms downstairs from feeling dark. Upstairs, all the wood trim is painted in the same off-white, leaving the choice of wall colors up to Mary while ensuring a flow through the rooms.

For the landscape, want and need were the same: low maintenance. “I see no reason to grow grass on a 45-degree incline and then have to mow it,” Mary says. Though she’d love a cottage garden filled with blowsy flowers, she did not want to commit the time to it long-term. The yard is primarily a native shortgrass prairie with maple and oak shade trees, all designed to transition from sun to shade-tolerant savanna as the trees mature. Landscape designer Dan Peterson of Habadapt put in as much color as he could: red-twig dogwoods that stand out in the snow, sugar maples for fall color, forsythia for spring, plus pink hydrangeas and prairie flowers for summer. Swales in the yard allow runoff to zigzag down the yard, making it self-watering. A small vegetable garden is easily managed from the sunken patio. The recessed patio’s floor and its retaining walls capture the house’s thermal mass for an extended growing season.

The interior is all that the couple had hoped for. Woodwork downstairs matches that in the 1912 Foursquare: quarter-sawn oak for the living room, dining room, and kitchen, with flat-sawn oak in the pantry, den, and powder room. Mary specified granite countertops “for the way Ray cooks—he can put a 500-degree cast-iron pan on it.” The absolute-black granite with a honed finish has the look of soapstone, and is the same choice they’d made in their previous house. North Prairie Tileworks in Minneapolis made the deep blue field tiles to set off a decorative tile Mary had bought in England.

The blue guest bathroom, also accessible for Ray, was designed around a marble sink console that looks like an Edwardian-era dresser—which came, oddly enough, from Pottery Barn. The master bath has dark granite countertops to absorb coffee spills.

“Our architect never gave us one bad word of advice,” Mary says. “Early on, he said that we’d be living with the interior fittings and finishes we chose for a long time, and that we’d be happier with the house if we chose better quality over more square footage. I couldn’t agree with him more.”

An Accessible House

What used to be called handicap-accessible or disabilities design is now an aspect of universal design, which seeks to make buildings and products function better for everyone: children and grownups, short and tall and vision-impaired. Here the house was set into the hillside for a modest street presence, yet it offers access to the garage, the porches, and even a backyard patio. If the program called for a “retirement home,” the result is much more. Features include:

-On-grade garage and secondary entry door

-Patio accessible from a door with a compliant threshold

-Wide hallways, passages, kitchen clearances

-Full-size elevator

-ADA-compliant bathrooms

The contractor used low-clearance thresholds and wide doorways for potential wheelchair access. A screened porch is immediately outside the kitchen (with a pass-through) and opens to the grille deck. The dining room door also leads to that deck. “Our contractor Ben Quie has enjoyed treats from Ray’s smoker over the past 20 years,” Mary says, “so he was motivated to make it easy for Ray to tend the barbecue ribs. On the porch, we have a shelf level with the kitchen windows so Ray can just set out the gin and tonics.”

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.