Arts & Crafts Genre Lighting

As scholarship has grown and the revival has embraced many diverse roots, we better recognize sub-styles in work that emerged during the first and second decades of the 20th century in Arts & Crafts lighting.

American Arts & Crafts lighting begins with East Coast Mission (or Craftsman) work, as well as that of the Midwest Prairie School. It segues to hammered copper and mica art pieces. Fixtures betray Asian influence, most famously in the work of California architects Greene & Greene. California motifs abound. Finally, we have the Hollywood-generated Storybook style that was popular through the 1920s.

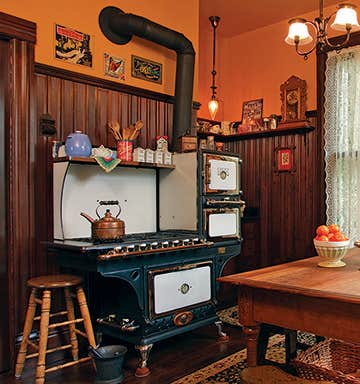

Many of these Arts & Crafts-related styles are rooted in a particular place or associated with a specific type of architecture, or even with an individual designer (Charles Rennie Mackintosh, for instance). What we call Craftsman or Mission, for example, is strongly associated with Gustav Stickley and the Roycrofters on the East Coast. It features an unadorned medievalism. Most “Mission” chandeliers, sconces, and pendants are crafted of metal—occasionally even copper, though copper was less commonly used during the period. On many fixtures, mounts and light housings are rectilinear with sloping, four-sided hipped-roof or pyramidal tops. Bracket arms, or even the overall fixture or lamp base, may be curved or rounded. Details include exposed rivets, windowpane overlays, and square cutouts grouped in threes and fours.

Mission lighting is typically fitted with mica (more popular in lamps than fixtures), slag glass (semi-opaque art glass in earth colors like streaky white, buff, mottled green, and brownish-orange), or lighter art glass in bright, clear colors. Shades range from simple clear or frosted glass to mouth-blown iridescent glass.

Prairie lighting is easy to confuse with Mission because both use square and rectangular shapes. Today’s manufacturers tend to use interchangeable bases, in fact, and nudge toward a “style” with the choice of shades. Prairie style, of course, is related to the planar, modern architecture developed by Frank Lloyd Wright and other Prairie School architects. Prairie fixtures tend to have sharply rectilinear mounts and housings. They are often constructed with strong horizontal and vertical lines, which, when they intersect, create triangles, windowpane patterns, and intricate geometric designs in art glass. Many of the best fixtures borrow heavily from the window and furniture designs of Wright and Louis Sullivan.

In California, the brothers Charles and Henry Greene, who had been trained as architects in Boston, began to use Japanese-derived elements after about 1904. In their “ultimate bungalows,” woodwork and lighting were often integrated. These influential fixtures were characterized by subtle curves, like the slight jog of their “cloud-lift” motif, along with pagoda-like tops.

Hammered copper with mica is often considered the epitome of Arts & Crafts lighting. The genre is most closely associated with Dirk van Erp, a Dutch–American artisan working in the Bay Area. He is known for his extraordinary table lamps with gourd-like hammered and patinated bases and cone-shaped mica shades with metal strapwork. Van Erp’s associate Auguste Tiesselinck came up with the idea of silhouetted cutouts (or filigree) that lay on top of the mica, a detail that would be picked up in the Storybook style that emerged in the 1920s.

Storybook lighting has fairytale connotations, and like fairy tales, this genre can be dark and brooding or whimsical. On one side are those medieval, black-iron fixtures that look as if they came from Moorish Spain or England’s Dark Ages. Typical are both “torches” and cylindrical lanterns topped with a witch’s cap. The look is used on everything from sconces to chandeliers. While black iron lights can be fitted with any kind of glass from slag to seedy, the classic Storybook light (popularized in 1920s Los Angeles neighborhoods such as Los Feliz) wears orange mica.

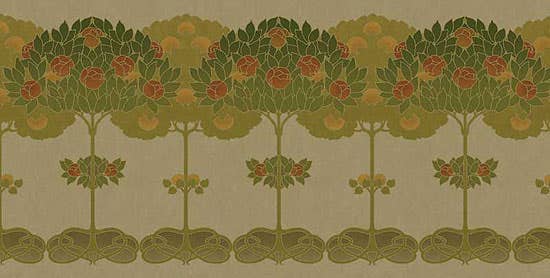

On the lighter side, metal finishes are less brooding and decoration more whimsical. Finishes range from rustic (literally rusty) to antiqued copper or patinated green-gold. Decorative touches include grillwork (sometimes bent or dented to suggest great age), and straps or ribs that end in scrolls. Overlays include Gothic arches; metal filigree silhouetted against the art glass or mica may feature flowers, birds, butterflies, or tree shapes.

Style Selection

Arts & Crafts lighting is itself art, and as such, a lamp or fixture can be appreciated on its own, regardless of the context. Still, some lighting genres just beg to be fitted into certain houses. If you are looking to underscore a certain style, and especially if you are buying a lighting suite, start here:

Medieval Revival black-iron fixtures match up with these house styles: Tudor–Gothic, Tudor-inspired Shingle Style, Spanish and Mediterranean Revival. Note that some fixtures lean toward old French and English antecedents, while others have a Hispano–Moresque flavor.

Prairie Style fixtures, whether with wood or metal bases, feature abstract and geometric forms and art glass. They match up with Prairie-inspired houses, many Foursquares, Midwest bungalows, and ranch-style houses.

California styles are always at home on the West Coast and in bungalows. The simpler forms look good on, say, porches from coast to coast.

Greene & Greene-inspired lighting brings Japanesque forms that complement California bungalows, Exotic Revival rooms, and even Prairie houses.

Storybook fixtures are perfect for steep-roofed Tudors, towered Norman Revival houses, and quirky bungalows. Lighthearted “Cottage” fixtures match up well with Shingle Style, Dutch Colonial, and Cotswold-style houses, as well as bungalows.

Mary Ellen Polson is a creative content editor and technical writer with over 20 years experience producing heavily illustrated know how and service journalism articles, full-length books, product copy, tips, Q&As, etc., on home renovation, design, and outdoor spaces.