Decorative Motifs

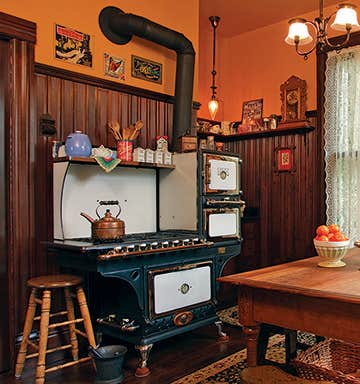

Certain motifs repeat in the decorative arts movement and its revival. These may be ancient, like the Celtic knot, or simply pretty and easy to stylize, like the iris. Most of the motifs come to us from nature and moderation and balance is key when decorating.

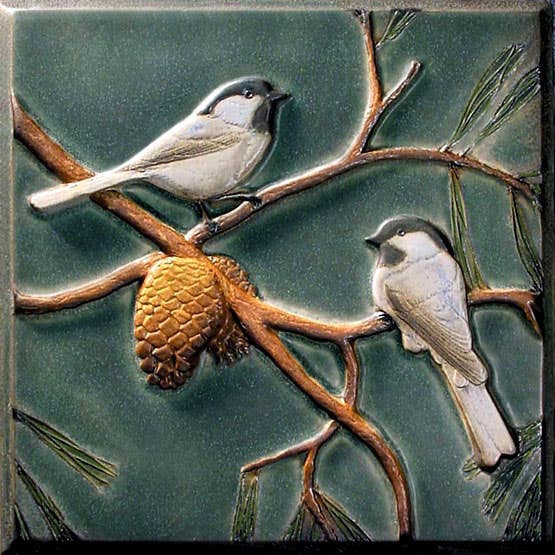

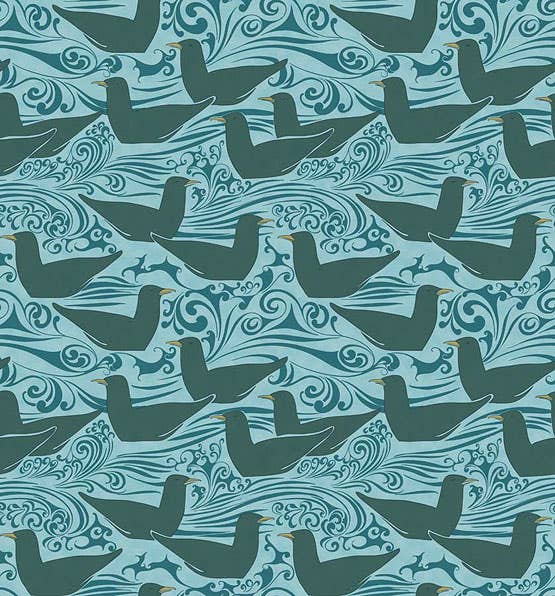

Benign bird species like sparrows, wrens, and robins appear in the swirling flora-and-fauna designs of William Morris and in the nursery-like designs of C.F.A. Voysey. (Both were influential designers of the British Arts & Crafts movement.) Sparrows, cranes, and owls are often Japanesque in their rendering.

In this period, naturalism was undoubtedly the point of using birds, more than their ancient symbolism (which is understandably connected to heaven and the soul). Nevertheless, even a tile or an embroidered pillow will create a response depending on the creature shown: the mystical raven, a summer songbird, the carefree gull, or a chickadee, cheerful and plump.

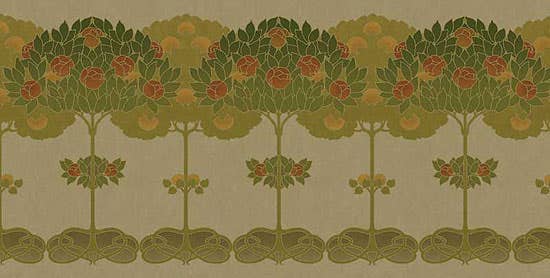

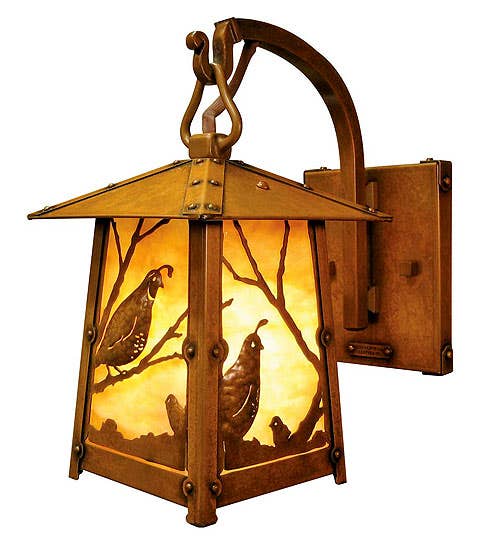

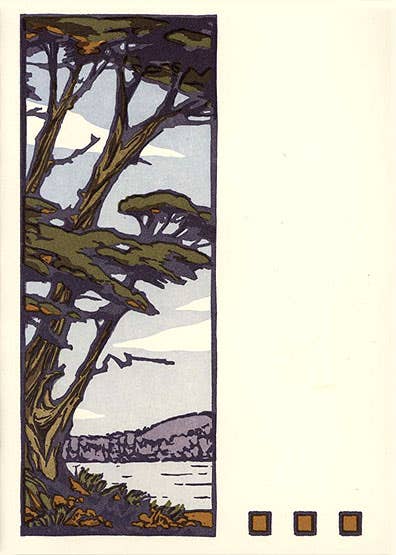

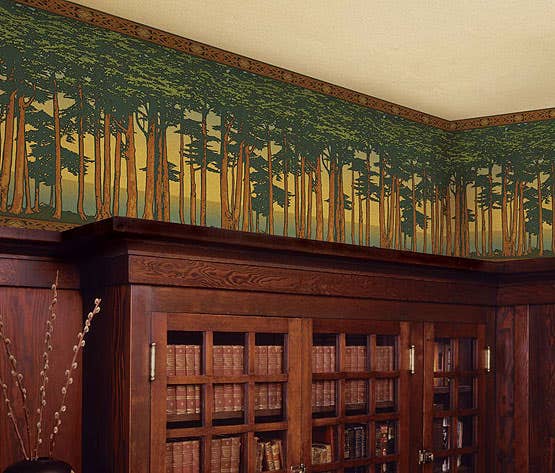

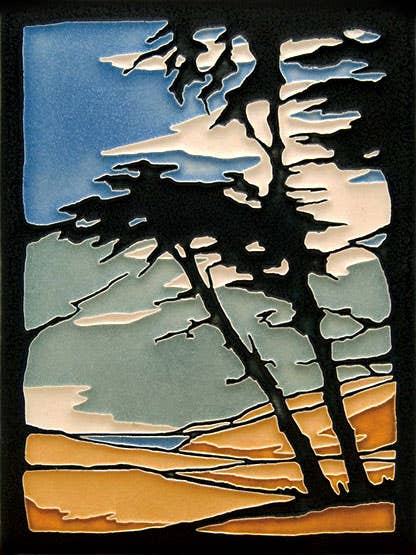

The cypress tree, stylized or in silhouette, is a popular image of the revival. The Monterey cypress (Cupressus macrocarpa) is a California Arts & Crafts icon. In fact, the Pasadena-based lighting company Arroyo Craftsman chose the tree for their logo. A taller coastal cypress, familiar at Lands End, the park overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge, inspired a Bradbury wallpaper frieze.

A century ago, Louis Comfort Tiffany used stylized cypresses on the courtyard walls of his house; he in turn was inspired by Islamic design in Spain. The tree shows up in 17th- and 18th-century Iranian (Persian) art, and in 16th-century Japan. In Native American, Muslim, Christian, Egyptian, and Ancient Greek symbolism, the (European) cypress was associated with eternity. More recently in Western culture, the Monterey cypress suggests solitude, and thus freedom. Symbolism aside, artists choose the windswept tree just for its beauty.

And then there’s the ever-popular ginkgo leaf. It was once thought extinct by Westerners, having disappeared from Europe and the Americas millions of years ago, but was cultivated in China and introduced to Japan around 1200 A.D. The trees may live over 1000 years and are revered for their strength and longevity. After four ginkgoes survived the atomic blast at Hiroshima in 1945, the trees came to symbolize hope and peace.

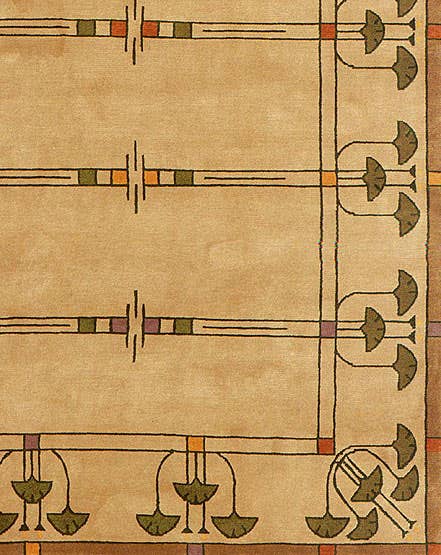

With a natural resistance to diseases, insects, pollution, and even fire, ginkgos are prized as street trees and in parks (as well as in Japanese-style gardens). Ginkgo biloba (e.g., bi-lobed) trees have a notched leaf that is aesthetically pleasing and easily stylized. Depictions have long been popular in Japanese art and in Arts & Crafts, Prairie School, and Art Nouveau design.

Here are three motifs we’ll be describing soon:

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.