The All-Important Wall Frieze

The decorated interior wall frieze came into its own during the Victorian era, and was adapted for the lowered ceilings and simpler treatments of the Arts & Crafts period.

The high ceilings (nine feet or more) in late Victorian-era houses called for wall division to balance the room’s proportions, bringing the eye down from the ceiling. The popular tripartite treatment called for a wainscot or dado, a field or fill area, and a narrow frieze above the picture rail, each decorated differently. The frieze might be covered with an embossed material like Lincrusta; hand-painted, stenciled, bordered or striped; or embellished with detailed plasterwork. Uplifting mottos and quotations were favored in dining rooms and libraries.

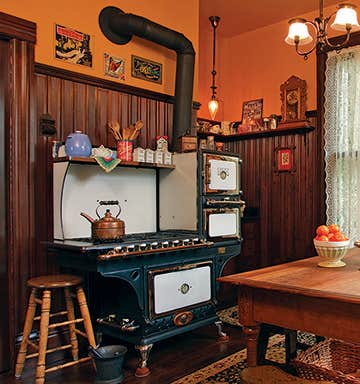

Still, the frieze was not abolished with the lowered ceilings of bungalows and Craftsman houses. Rather, the frieze was often a deeper section of upper wall surmounting a high wainscot and plate rail. The frieze could be 14" to 27", or even deeper. In rooms without a wainscot, the frieze survived as a band above the picture rail, with a single wall fill treatment running to the baseboard.

Woodwork

With the preponderance of woodwork in Craftsman homes—such as colonnades, inglenooks, and high wainscots—often the only wall surface left for embellishment was the frieze, and so it became a dominant decoration in a room with wood-clad (or painted) walls below, and little ceiling ornamentation.

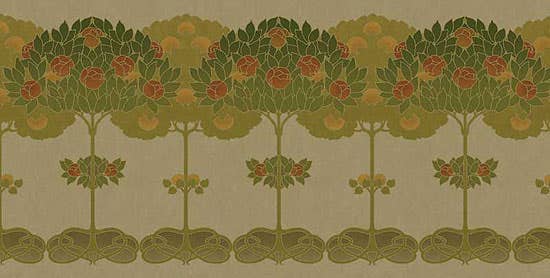

Recommendations for decoration included specially designed wallpaper friezes, with patterns that might be geometric or foliate, or presented as an abstracted landscape, or with pendant ornaments that repeated regularly around the room. Decorating in the Arts & Crafts era brought nature indoors, so vines and abstract floral designs were popular, as were idyllic woodland scenes, animals, and sea motifs. For bedrooms and in Colonial Revival treatments, a plain painted frieze, often in the same off-white color of the ceiling, was popular.

Burlap was another suggestion (not only between wainscot battens but alternatively in the frieze), as was simple hand stenciling. Stencil patterns were simplified versions of wallpaper motifs. To blend with natural-finish woodwork in Arts & Crafts houses, dominant colors in the frieze moved toward warm and earthy tones, with dull greens, browns, deep grey-blues, russet, and gold all popular. The wall area below the frieze, when a high wainscot was not present, would be treated simply, with a matte paint finish or perhaps striped or covered in a very plain coordinating paper.

Brian D. Coleman, M.D., is the West Coast editor for Arts & Crafts Homes and Old House Journal magazines, our foremost scout and stylist, and has authored over 20 books on home design.