Revival Interiors

In this chapter, you’ll also find period textiles that add layers of color, patterns, and textures to rooms inspired by the original Arts & Crafts movement.

Enjoy the resurgence in beautiful treatments for walls and ceilings—in wallpaper, paint, metal, plaster, and wood. In this chapter, you’ll also find period textiles that add color, pattern, and texture to rooms inspired by the original Arts & Crafts movement.

Bungalow-era interiors have been described as simple—even dark and monastic—but by modern standards they are fully decorated. Woodwork and trim, wallpaper and paint, rugs and pillows and portières all contribute to the cozy effect. In a departure from Victorian interior decoration, bungalow writers frowned on the display of wealth and costly collectibles. Rather than buying objects of obvious or ascribed value, the homeowner was told to look for simplicity and craftsmanship: “a luxury of taste substituting for a luxury of cost.”

But keep in mind that both Greene & Greene’s Gamble House in Pasadena and a three-room vacation shack without plumbing were called bungalows. The finest examples of Arts & Crafts handiwork found a place in the bungalow and other homes of the era.

Walls were often wood-paneled to chair-rail or plate-rail height. Landscape friezes and abstract stenciling above a plate rail often were pictured. Dulled, grayed shades and earth tones, even pastels, were preferred to strong colors. Plaster with sand in the finish coast was suggested.

Woodwork could be golden oak or oak brown-stained to simulate old English woodwork . . . or stained dull black or bronze-green. Painted softwood was also becoming popular, especially for bedrooms.

Writers advocated the “harmonious use” of furnishings. Oak woodwork demanded oak furniture, supplemented with reed, rattan, wicker, or willow. Mahogany pieces were thought best against a backdrop of woodwork painted white. A large table with a reading lamp was the centerpiece of the living room in these days before TV.

The Walls & Ceiling

Wallpaper continued to be popular throughout the Arts & Crafts period and beyond. Gone was the multi-patterned, tripartite treatment (dado, fill, frieze) of the Victorian era. Treatments now included panelized walls—with embossed wallcovering, paper, burlap, or stencil designs between moldings or battens. Most popular was the embellished frieze in the area at the top of the wall just under the ceiling.

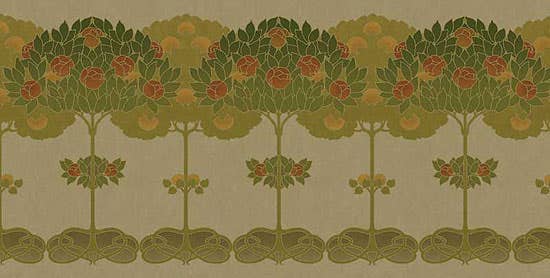

One classic was the pendant frieze, a border accented with geometric focal points that drop down at regular intervals. The landscape frieze was also popular: trees on a continuous horizon, a riverbank at twilight, sailing ships silhouetted between waves and sky. Perennially popular florals include stylized lilies and roses (and also wisteria, nasturtiums, and other flowers). Frieze depth ranges from as little as 8" to 16", 24", or 27". (You can add borders to a frieze paper to adjust the depth.)

Ceilings also got decorative treatments. Rarely were they painted white; a “plain” ceiling might be painted a peachy beige or a light tint of the wall color.

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.