The Finished Wall

Once a cheap and practical wall covering considered fit only for back-hall and service areas, beadboard now appears front and center in many high-end bathrooms and kitchens. But it’s just one of many legitimate wall treatments for Arts & Crafts homes.

Wood strikes a chord in the American heart. It’s a rare homeowner who doesn’t prize hardwood floors, and for many, wood paneling and related wall treatments are the ne plus ultra of the Arts & Crafts home. As Gustav Stickley wrote a century ago, “no other treatment of the walls gives such a sense of friendliness, mellowness, and permanence as does a generous quantity of woodwork.”

Wood paneling may be one of the signature statements of the Arts & Crafts period, but for the most part, treatments were simple and economical. One of the plainest of these, beadboard, is enjoying a comeback in all sorts of settings. As a product of late- Victorian millwork, beaded boards are relatively thin (3/8” to 5/8” thick) pieces of tongue-and-groove lumber with a side bead or convex molding along one interlocking edge. (The bead is actually a device to distract the eye from gaps that form as the wood shrinks and swells seasonally.)

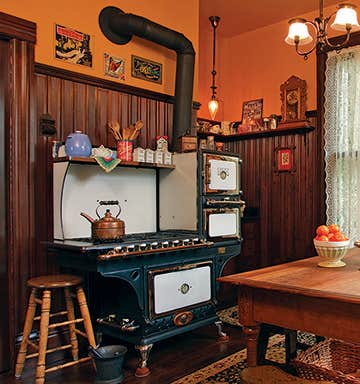

Inexpensive even when machine-cut from Southern pine and cypress, beadboard was ubiquitous in back-of-the-house rooms frequented by servants, like the kitchen and utility areas. Beadboard ceilings are a standard treatment for porch ceilings, and in seasonal cottages, the entire house might be paneled in beadboard. Today, beadboard is a contemporary favorite in kitchen and bath renovations at all price points. It can be run vertically or horizontally, used as a high or low wainscot or sparingly as an accent, or cover walls and ceiling of an entire room.

Beadboard was historically considered low style, and high-style paneling was reserved for the more formal parts of the house: the dining room, parlor, or staircase. Despite its elegant appearance, board-and-batten paneling is fairly simple to install. Wide (12”) planks of oak, fir, red gum, or cypress are butted together vertically; the joints are covered with narrow battens (2½” to 4” wide strips of wood). Topped with a molded plate rail, this installation was a straightforward means of creating the look of expensive, three-dimensional paneling.

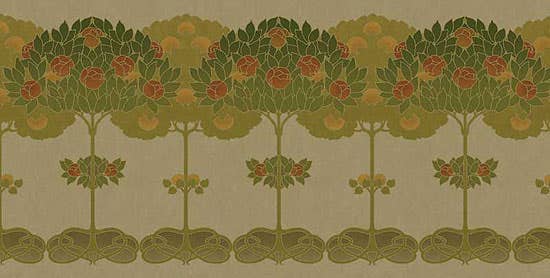

Variations on the board-and-batten theme include what was called “skeleton wainscot,” where panels between the battens were not wood but rather covered in leather, faux leathers, embossed wall coverings including Lincrusta and Anaglypta, and the less expensive classic, burlap. In such a treatment, regularly spaces battens are applied directly to the wall over applied panels of a textured wall covering or fabric.

A century ago, the burlap applied to such walls was paper-backed; modern substitutes include dense, tightly woven fabrics with a significant linen content, such as linen union or Bungalow cloth. You can get a similar effect with less fuss by simply painting the lower portion of the wall in a color of your choice, perhaps adding a texture as by combing, then applying battens and a plate rail.

Gustav Stickley himself recommended leather as both rich and unobtrusive. While leather is certainly historically correct, many faux leathers (sometimes described as “elephant hide”) were used, too. Invented in the late 1800s, both Lincrusta (a linoleum-based wall covering) and Anaglypta (one type of embossed paper) offer a high-relief finish. Traditionally wood paneling was finished with shellac, which darkens with age, and any of the embossed mediums can be stained, painted, glazed, or antiqued to dramatic effect.

Mary Ellen Polson is a creative content editor and technical writer with over 20 years experience producing heavily illustrated know how and service journalism articles, full-length books, product copy, tips, Q&As, etc., on home renovation, design, and outdoor spaces.