Artist Glenn Pankewich

Artist Glenn Pankewich has been restoring, interpreting, and finding new inspiration in the art glass of a century ago.

Of the hundreds of artisans who create stained glass objects in the style of Louis Comfort Tiffany, Glenn Pankewich may be the only one who rolls his own. “What was foremost at Tiffany was the quality of the glass,” says Pankewich, who got his first look at a real Tiffany lamp at age 14. That was 40 years ago. Since then he has emerged as one of world’s best Tiffany restoration artisans, working on lamps worth as much as $1 million. “Restoration is where you learn how to do it right,” he says.

Pankewich had no formal training other than apprenticeship to the shop owner who introduced him to that first Tiffany lamp, a 16" Dragonfly. He says he gets his artistic bent from his father, an oil painter and craftsman known for his sense of humor. (The elder Pankewich liked to spray the aroma of the subject on his paintings—onion juice on a still life with onions, for example. “That’s how nuts he was. Almost a George Ohr type of guy.”)

Early in his career, each summer Glenn would board a bus with a $55 ticket good for two months’ travel anywhere in the U.S., to look for usable glass. He’d come home dissatisfied with the quality of glass available. Then he heard about a German glassmaker in northern Florida who was experimenting. “I hooked up with Greg Lins and began to create fantastic glass,” says Pankewich, who ended up running Lins’ foundry during the 1980s. Although he made close copies of Tiffany originals early on, most of what he makes now are his own inspiration—and he signs them. “I don’t want them to be confused with Tiffany antiques.”

The Chemistry of Glass

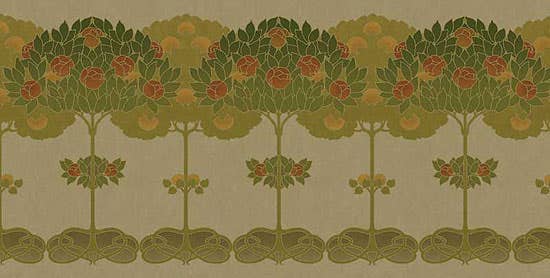

At its most basic, glass is a mixture of sand, soda, and lime. Glassmakers create a dizzying array of effects by adding other compounds—suspending tiny, light-blocking particles, for instance, to create opaque glass. Handmade glass that approaches the inventiveness of real Tiffany glass may contain opals, oxides, even gold and silver. The way the glass is manipulated in the furnace and on the rolling table, too, can add variations in color and characteristics that can be jaw-dropping in the hands of an artist.

Glass types Pankewich produces in his self-imposed three-sheet-a-day quota include confetti, mottled, scum (or hazing), and drapery glass. Confetti glass, for instance, is made by blowing a bubble of hot glass in one of several colors. After allowing the bubble to cool, Pankewichshatters it into a bucket. The small chips that result are then scraped onto a flat surface and hot glass is rolled on top, embedding the chips in the glass sheet.

Read about Old Leaded Glass

Making a Glass Shade

Pankewich makes his own glass, copper foil, solder, and patinas. Not surprisingly, he’s adopted many of the same design and construction techniques used by Tiffany a century ago. Once he has a concept for a lamp in mind, he makes a mold in the desired shape for the shade. Many of his reproductions are made from originals. “You can actually pour plaster of Paris into a half-million dollar lampshade,” he says.

The next step is to create artwork—a drawing called a cartoon—on top of the mold. Pankewich applies a second skin of cellophane over the cartoon, fastening it with masking tape and paper to take on the contour of the mold. He retraces the design through the cellophane layer. Then he peels off the cellophane sketch and cuts it up with an X-acto knife. “Now you’ve got segments that you can lay on the surface of sheets of glass,” he says.

To join the pieces of glass together, they must first be wrapped in copper foil, creating channels that the lead/tin solder can adhere to. Pankewich makes his own copper foil so that it fits the varied thicknesses of his handmade glass. Once the glass—still on the mold—has been soldered together, he heats the shade to 100–120 degrees, just enough to melt a resist layer of beeswax between the mold and the glasswork, freeing the shade. The lampshade is then electro-plated in copper solution, coating the solder. The final step is applying a patina to the solder and any other metal parts. Using copper and sodium chloride, the process mimics the naturally oxidized finish on a copper faucet: green with red and yellow undertones.

Glenn Pankewich, Tiffany Studios Lamps & Windows, Jupiter, FL (561) 575-4721, tiffanystudioslamps.com

Mary Ellen Polson is a creative content editor and technical writer with over 20 years experience producing heavily illustrated know how and service journalism articles, full-length books, product copy, tips, Q&As, etc., on home renovation, design, and outdoor spaces.