Wallpaper, 1901–1945

Wallpaper designs of the Teens and Twenties often lagged behind the high-style Arts & Crafts designs we find fashionable today. Here’s an introduction that includes florals and oatmeal papers, and even the Colonial Revival influence.

In bungalow neighborhoods across North America, restored homes resonate with painstakingly matched furniture, carpets, wallpapers, even breakfast dishes in documentary patterns. But despite the thorough documentation (and reproduction) of Arts & Crafts material culture, the reality was more varied. Families were rarely able to start completely fresh when furnishing a new house, even one as demanding design-wise as a bungalow. Like many of us today, people took their old furniture with them, carting Aesthetic-movement parlor furniture or Renaissance Revival sideboards into a new home. Taste in interior decoration followed, bringing Victorian sensibilities in wallpaper and draperies along with the furniture. Although most period reproduction papers today are hand prints, the originals were almost exclusively mass-market papers, sold at hardware, paint, and wallpaper stores, or by mail order.

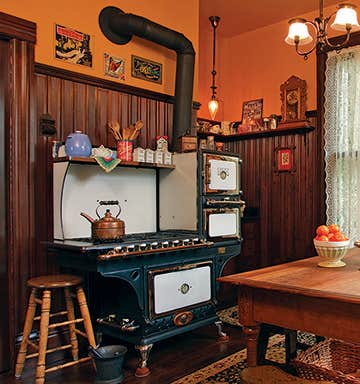

Thumbing through the old catalogs today, it’s immediately apparent that the offerings for 1907 would have looked quite at home in the 1890s. Dark colors of burgundy and green, sometimes offset with cream grounds, were embellished by swags of roses, and decorated further with metallic inks in gold, bronze, copper, or silver tones. The notion of wallpaper collections of specific design types had yet to appear. Kitchen papers—including “granite” designs that wouldn’t show dirt and “Sanitary” papers that were pre-varnished for washability—were intermingled with posh parlor papers, or Japanese-inspired cloud design ceiling papers, printed in softly reflecting mica inks.

With such a wealth of choices, most homeowners would be guided more by personal choice rather than by designs that matched the style of their home. In other words, a housewife who liked a wallpaper with sprigs of lilac joined with silk ribbons would undoubtedly have triumphantly installed that paper in the bedroom of her bungalow.

The heavy Victorian patterns began to fade after 1907, disappearing altogether by 1917. Although we tend to think of the 1910s and ’20s as the heyday of heavily decorated, floral Arts & Crafts papers, striped papers were far more prevalent. About half of all wallpapers in 1920 offered some sort of stripe, often incorporating small floral or stylized decorations as part of the design. Creams, browns, and dark greens predominated, but vibrant turquoises, purples, apple greens, greys, and pinks were also common.

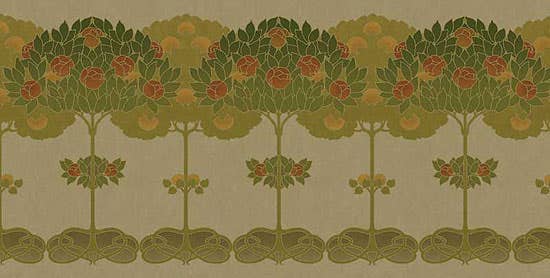

Where Victorian wallpaper borders of the 1890s were usually around 8" or so wide, by 1910, borders had doubled in width, often reaching 18" or 20" deep. In older homes, the picture moldings often had to be repositioned in order to accommodate the wider borders. Proportionally, these massive borders and matching sidewall patterns were reserved for the largest rooms in the house: parlors, libraries, halls, or occasionally large-size bedrooms.

Manufacturers also popularized several specialty papers that are still available today, including oatmeal (or ingrain) papers, and tapestry papers. Oatmeal papers were made with a wood pulp that was colored before it was rolled into paper, producing a lush, solid-color paper with a velvety finish. Oatmeal papers were frequently overprinted with Arts & Crafts patterns, and sometimes given “a sparkle from an expensive green bronze wash,” according to one catalog. Due to their rich coloring and printing effects, oatmeal papers were recommended for dens, libraries, halls, and dining rooms. The papers were often used as a fill between the vertical battens of a plaster wainscot, or on the walls above an all-wood wainscot.

Tapestry papers, introduced as early as 1908, simulated the look of fabric on walls. By the 1920s, at the height of their popularity, tapestry papers in patterns of overlaid leaves, grape vines, or other fruit rivaled striped papers for dominance. Like oatmeal papers, tapestry papers were most frequently found in halls, dining rooms, dens, and libraries.

Even at the height of their popularity—around 1921—Arts and Crafts wallpapers never cornered more than one-third of the market. More often than not, homeowners would simply have picked out papers that they liked. But today, blessed with hindsight, we have the luxury of reaching back and plucking the best history has to offer to complement our houses. Wallpaper reproductions, representing the purest of the historic designs, are more widely available than ever. And you can still select a paper just because you like it.

Stuart Stark is historian and proprietor of Historic Style historicstyle.com and Charles Rupert Designs in Victoria, British Columbia.