Revival Kitchens

Putting a sympathetic new kitchen into a bungalow is easier than remodeling a colonial or Victorian one. Even if you splurge on hardware and lighting, a true “period” kitchen is an easy and affordable room to re-create.

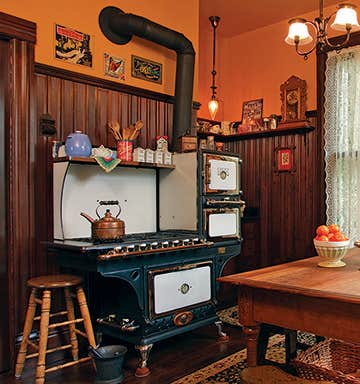

Original old-house kitchens were often plain and utilitarian—with painted cabinets, a floor of linoleum or softwood (or occasionally tile), and a washable wainscot of beadboard or white tile. Most bungalows, American Foursquares, and Tudor Revival houses had kitchens built for use by the housewife (not servants). Kitchens may have been small, but they were integrated into the main floor plan, and they had built-ins and electricity. Putting a sympathetic new kitchen into these houses is easier than remodeling a colonial or Victorian one. Even if you splurge on hardware and lighting, a true “period” kitchen is an easy and affordable room to re-create.

Many people remodeling older homes do not, however, want a bungalow-era kitchen. The kitchen is no longer a utility room, but the center of the house. It may have a second prep area, a wet bar, a household office, a breakfast area, and a TV. As in the past, related rooms include a back hall or mudroom, a bathroom, and one or more pantries. Whether you are building new or extensively, it makes sense to design a more public and “finished” kitchen. Arts & Crafts revival kitchens are often beautiful spaces with furniture-quality cabinets accented by art tile, handsome light fixtures, forged and cast hardware, and decorative textiles.

Still, you want the kitchen to fit the house. Don’t be tempted to over-scale the room. Before you assume you need to add on, try borrowing space from a back hall or pantry and keep to the original footprint. Additions should be proportionate to the house; sometimes just a few feet, bumped out on the rear or side of the house with windows for extra light, is enough. Keep it simple. The room will have a more timeless look if details are borrowed from historic kitchens, or the pantry or hall, rather than copied from high-style details in the dining room. Besides, a simple kitchen is easier to clean! Consider using several different counter surfaces. That’s historical, and it’s practical. Pick something nonporous near sink and stove, butcher-block for prep, perhaps a marble slab for baking or pizza making. You may even save money by purchasing remnant or salvaged material for small areas.

Common sense should prevail: Why spring for professional appliances if you eat out five nights a week and use a microwave on the other two? On the other hand, if you’re always in the kitchen making a mess, don’t use fussy, hard-to-clean details and materials.

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.