Today in East Aurora

Just after I moved to the village of East Aurora, New York, I had a curious experience.

East Aurora is home to the Roycroft Campus, a National Historic Landmark district. It is, as the website says, “the best preserved and most complete complex of buildings remaining in the United States of the ‘guilds’ that evolved as centers of craftsmanship and philosophy during the late 19th century.” Yet there’s more here than a museum-like campus or an American Arts & Crafts mecca for out-of-towners.

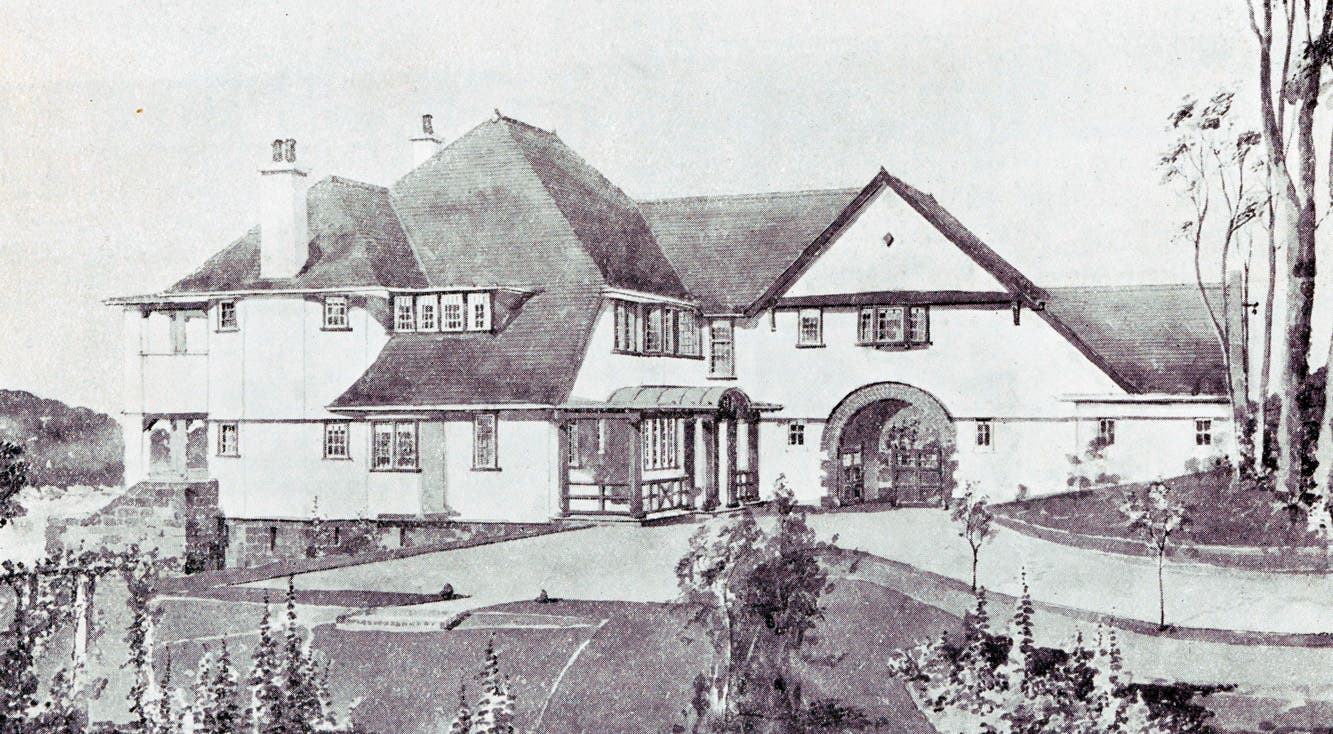

“The Roycroft,” as all the parts are collectively called, is a living and active part of the village. The exquisitely restored Roycroft Inn offers Friday-night jazz and is the go-to place for weddings; the best gifts in town come from the Copper Shop Gallery’s roster of expertly vetted Roycroft Renaissance artisans, The Roycroft Campus Corporation offers educational tours, artisan-led classes, and sponsorship events like the Native American dance performance that my son and I attended this summer. Then there are the renowned, biannual art festivals put on by the Roycrofters-at-large. The home of Elbert Hubbard, founder and presiding genius of the Roycroft movement, is open for tours. In other words, “The Roycroft” is big presence in a small town. It’s also something that definitely helped sway my family toward making East Aurora our home.

I heard similar “that’s Roycroft” references twice more: once while I was ogling a bungalow, another time a Foursquare. The casual but unembellished remarks, along with some general conversations about architecture and the festivals, led me to observe that a large swath of the village population knows that something important is in its midst, yet has no clear understanding of the larger Arts & Crafts movement, its ideals, or its more diverse architectural legacy. Don’t misunderstand me; I don’t mean to imply any judgment and certainly no condescension. The residents of East Aurora have been exposed to Arts & Crafts in a way that’s completely different from my own education. While I learned about Arts & Crafts and Roycroft as an adult, through my love of old houses, Roycroft is simply part of daily life here—background music, as it were. A bronze statue of Elbert Hubbard stands on the grounds of the middle school. The Roycroft Inn plays host to Santa Claus during a delightful Christmas Open House, free to the community. Our Town Hall, where kids sign up for swim lessons and T-ball, was the former Roycroft Chapel. Heck, even the trash receptacles along Main Street have Hubbard epigrams in gilded letters!

At first I was surprised to see Hubbard quoted on trash containers, but then I remembered that the man was nothing if not a populist: “No one but an aviator has the right to look down on others,” he wrote. Besides, the handsome wooden receptacles are the best-looking garbage cans I’ve ever seen.

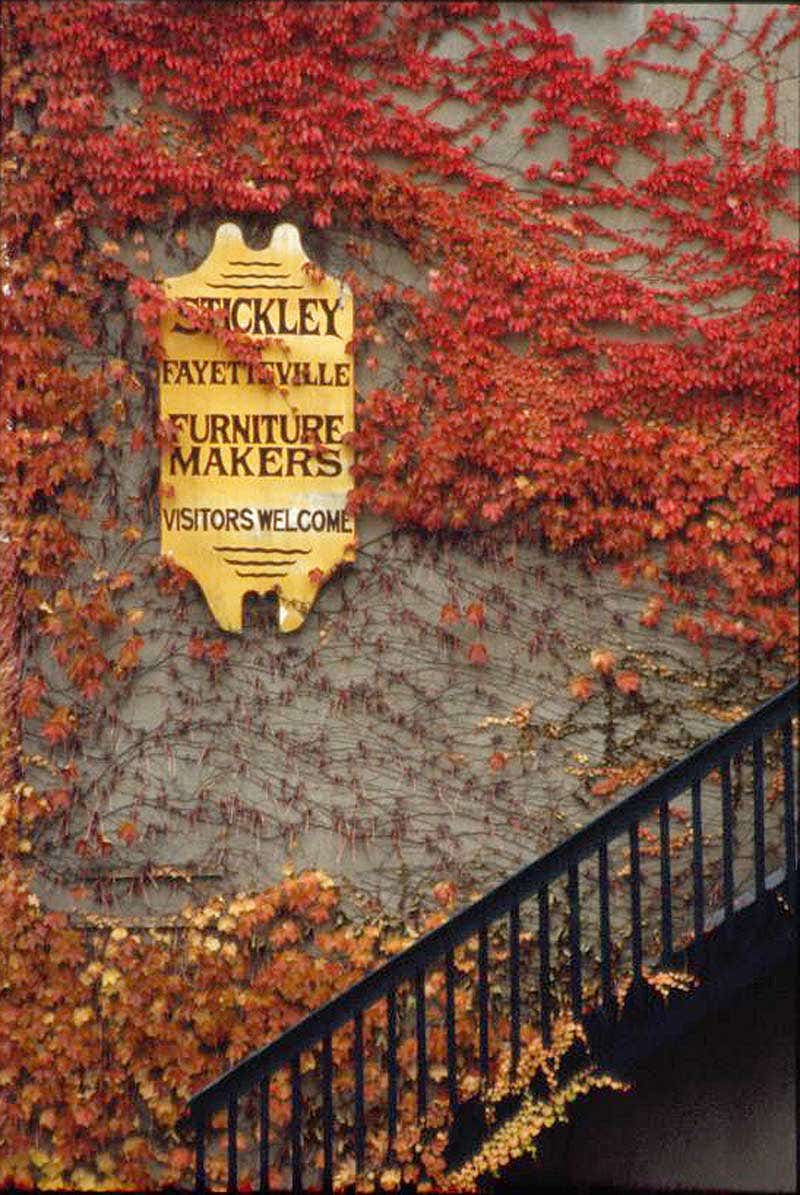

Still, I must admit that I catch of whiff of irony every time I see the distinctive A&C font, which was designed by Dard Hunter for old Roycroft publications, on signage used to shill everything from lawyers to liquor. This morning, I even noticed it on the police department’s K-9 Unit vehicle.

The ubiquitous use of the Roycroft font leads me to muse about a larger trend: Arts & Crafts design in commercial architecture. Perhaps the earliest example around here, a strip mall at the edge of the village, bears only the faintest resemblance to the historic Roycroft Inn. At the other end of the village (and spectrum) is a very thoughtful Arts & Crafts revival edifice built for a dentist. The most recent Arts & Crafts-evoking building here is a gas station.

Commerical Arts & Crafts

I call this movement Commercial Arts & Crafts—an oxymoron, perhaps. Now, commercialism played an undeniable role in the Roycroft community. Elbert Hubbard was an incredibly successful salesman. He used marketing techniques honed in the business world to sell Roycroft products, making his artisan community a financially successful enterprise. It’s hard to know just how far into the mainstream he might have brought the Arts & Crafts aesthetic, had he not died in 1915 aboard the Lusitania (after which, with the war and then the Depression, the movement lost steam). The fact is, though, that despite his zest for commercial success, the products Hubbard sold stayed true to the Arts & Crafts ideals of craftsmanship and beauty.

The ideals survive. There’s nothing sold in the Copper Shop Gallery or at a Roycroft festival which isn’t superb. And if I send my kid to a Roycroft summer camp, he’s not going to bring home spray-painted macaroni; more like a bowl crafted from sheet copper.

When it comes to the modern commercialization of Arts & Crafts, I ask myself: Am I being a snob if I don’t accept that A&C is (also) an appealing aesthetic that can be used by anyone for anything, regardless of its original intent? Do I have some particular right to it, just because I understand its origins? Is Commercial Arts & Crafts an interpretation, rather than a dilution? Hmm. As the immortal Meatloaf sings, “Two out of three ain’t bad.”

Getting back to the new gas station, which by its very nature is hard to make look “organic”: It’s clear the architect took pains with the design; stone piers house the gas pumps, and the neon sign is modest. Honestly, it is, overall, a good-looking structure. And, as my husband so reasonably points out, it’s so much better than what might have been.

If Elbert Hubbard came back, I wonder, and needed to gas up his beloved Yale motorcycle, would he choose to do it here? Or would he pick the functional gas station that squats in a streetscape of Victorian beauties, on what is clearly the site of a teardown?

I think I know the answer. After all, he was the man who advised, “Positive anything is better than negative nothing.” I feel just a bit dissatisfied with that motto, though—until I remember that Hubbard also wrote this: “Don’t take life too seriously—you will never get out of it alive.”

Catherine Lundie is a happily incurable old house addict. Lundie is the editor of Restless Spirits: Ghost Stories by American Women, 1872–1926. She holds a PhD in English with a specialization in 19th Century American culture and literature.