The Arts & Crafts Bedroom

Today’s excellent Arts & Crafts Revival has given us hundreds of options for bedroom furniture. Choose from reissues, adapted designs, and interpretive work. Furniture craftspeople are working in every idiom from Stickley to Wright to Greene and Greene.

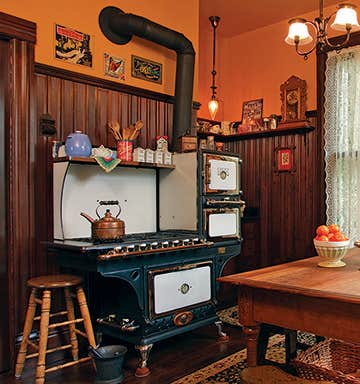

Say “Arts and Crafts” or “bungalow” and a very definite picture comes to mind: darkened oak, wainscot and plate rails, geometric pattern, and a dusky palette embracing amber, olive, and plum. We see the hearth, the wide frieze at the top of the wall, the slatted settles and tall dining chairs. Our vision may be cloudier, though, when it comes to bedrooms of the period. Bedrooms were, in general, lighter and simpler than rooms downstairs, often incorporating elements of the concurrent Colonial Revival.

Without a doubt, our choices today for furnishing a stylish bedroom are much greater than they were in 1905 or 1920. Sears, Roebuck sold a line of “mission” furniture, but only wealthy, individual clients were treated to designs by Greene and Greene or Frank Lloyd Wright. Now, the renaissance of Arts & Crafts philosophy and artisanry means that many different revivals are available to us: Stickley (including reproductions of Harvey Ellis’s inlaid designs), California, English Cotswold, Roycroft, Prairie School. Working in true Arts & Crafts tradition, today’s furniture makers offer new and interpreted designs, often with Scots–English or Asian leanings. The diversity of designs is apparent.

It’s instructive to look at original bedrooms of the Arts & Crafts period; some of them survive and others are documented in various books. Adopting the era’s sensibility will probably save you money, as bedrooms by the period’s tastemakers are startlingly monastic. This is true even in Wright’s Prairie houses and Greene and Greene’s sprawling bungalows. At the Gamble House, beautifully detailed bedsteads are all the more sculptural against plain carpeting, neutral walls, and the simplest of lighting fixtures. Stickley’s The Craftsman magazine showed small bedrooms like monks’ cells, with monochrome walls and plain oak furniture.

Light fixtures were inconspicuous. Stickley’s drawings often show a plain, utilitarian wall bracket or sconce over the head of the bed. Window curtains were practical panels hung from rings, often with a short valance and perhaps sheers over the glass. (Something I noticed in reviewing many photographs, old and new: original period bedrooms seem generally rather dark, with little regard for the view outside; revival rooms are more likely to have windows as a focal point, and even French doors!)

Upstairs rooms were historically trimmed out in softwoods. It was intended that this trim would be painted with an “enamel” of medium gloss. (Consider a very off-white hue in a beige, latte color.) Rugs and wallpaper or a paper frieze were optional. Stickley showed simple stenciling, and plain bordered carpets as well as Indian and ethnic scatter rugs.

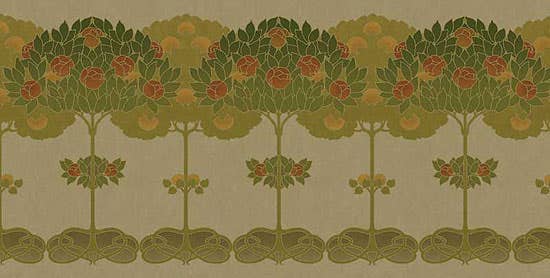

Other books and periodicals of the times show lighter, somewhat more feminine rooms with pastels and classical moldings. Then as now, textile and wallpaper patterns designed by William Morris work equally well as the backdrop in English art-movement, Colonial Revival, and Arts & Crafts rooms.

Bedrooms were small, often 11x12 feet or so. (They were somewhat larger in Stickley’s “Craftsman Homes” models: 10 x 14 for children and servants, up to 15x20 for master bedrooms.) The living and dining rooms were characteristically dark, but bedrooms were often bright. The bedroom might have paneled walls, particularly in houses built before the First World War, but upstairs this woodwork would have been painted a cream color. (Dark-stained paneled walls today are probably the result of a late-20th-century stripping job.) By the 1920s the paneling was gone and the plaster wall painted a light color, or cheerfully papered. By the ’20s, too, Colonial Revival sentiment had brought “colonial” colors and wallpaper patterns to many bungalow bedrooms. Quilts were popular both as “early American” icons and products of art-and-craft. Here is my impression of the quintessential Craftsman room, so often seen in Gustav Stickley’s The Craftsman magazine:

The rectilinear Stickley dresser is laid with a narrow scarf, perhaps plainly embroidered in one or two colors at the ends. A mirror above the dresser hangs by chains from the picture rail. The bed wears a plain bedspread, not white but not a dark color; it may have a border; it is tucked around the pillow and goes almost to the floor. No throw pillows, bolsters, or bedskirts are in evidence. A plein-air landscape painting hangs, again from short chains, over the head of the bed. The rug, covering most of the center of the room, has a plain, medium-tone ground with a border made up of one or more lines. An oak or wicker chair stands near the window. If there is a desk, it is small. If the room is large, an oak dressing screen softens one corner.

At Stickley’s own family home in New Jersey, the girls’ bedroom (which has been restored to its 1911 appearance) is a little fancier, though still spare and architectural. It is anchored by a large, modern fireplace clad in blue Grueby tiles. The ceiling is finished in light-grey sand paint, the walls in silver-grey grasscloth. The floor is stained brown, as is the linear trim, but sashes are cream. The furniture is from Stickley’s more decorative marquetry line, and there is an oriental carpet with light colors.

In truth, Gustav Stickley didn’t sell all that much bedroom furniture. (A website antiques dealer recently posted, “Gus bedroom furniture is always hard to come by . . . ”Many of the bedroom pieces available today came from L. and J.G. Stickley, whose company eventually absorbed Gustav’s.) Purchasers were more interested in outfitting their public rooms in the new style, so bedrooms invariably got the Renaissance Revival or populist “Eastlake” bed and dresser from Mother’s house. Ingrain carpeting, laid wall to wall in sewn-together strips, was still around. And many people just preferred Colonial Revival in the bedroom, especially in the years following the War.

What is the right “dialect” for your Arts & Crafts bedroom? Region plays an important role, but so does taste. Does the house lean toward low-slung, modern geometry of the Midwest Prairie Style? This kind of furniture often works well in American Foursquare houses with strong horizontal emphasis. Do you gravitate toward the more sculptural California furniture, or a Spanish-influenced Southwestern look? The most popular vocabulary, then and now, has to be the uncompromising lines of Stickley’s and Hubbard’s East Coast Arts & Crafts, the standard choice for those smitten with period bungalows.

If you prefer a rather pure American Arts & Crafts look, keep three words in mind: architectural, monochromatic, and simple. (Gustav Stickley called for bedrooms to provide “a harmonious environment.”) Arts & Crafts was a strongly architectural style; as in living and dining rooms, angularity and long lines appeared in the bedroom. Except in the rare case when an Art Nouveau influence crept in, curves were few. Many period images show a stained wood picture rail at roughly the height of window tops, creating a strong horizontal accent. Occasionally the frieze section above the rail was painted in a complementary color, or stenciled or papered. (Wallpaper, applied from baseboard to ceiling, was seen more commonly after 1920.) Ceilings were invariably light and plain.

Those looking for more ornamentation or femininity while staying within the “art movements” might consider touches of Art Nouveau. Sinuous lines showed up in headboard design, frieze decoration, and carpets.

Very different, but still in the Arts & Crafts tradition, is the English Arts & Crafts style. You may be working with a strong English element in, say, an Arts & Crafts-influenced house with late Queen Anne, Shingle Style, or Tudor elements. And many houses of this period were transitional. Their living and dining rooms may have Arts & Crafts elements, while the bedrooms would be better given a more traditional treatment, in keeping with the Colonial Revival style.

Selected Sources

artistcraftsman.net • T. Stangeland’s California designs

berkeleymills.com • Interpretive; Asian influence

coldriverfurniture.com • A&C beds, cradles, and case pieces

missionconceptsinc.com • Slat and Bungalow beds

kevinrodel.com • Custom A&C bedroom furniture with Glasgow, Asian leanings

sawbridge.com • Various lines with Prairie, Craftsman, interpretive designs

stickley.com • Reissues of Stickley, H. Ellis, and Roycroft designs, cherry as well as oak

swartzendruber.com • Craftsman and Prairie bedroom furnishings

thejoinery.com • Cherry and mixed woods; Mission, Asian beds, nightstands, chests

thosmoser.com • Interpretive designs with a Modern edge, including Bungalow bed and Japanese designs

voorheescraftsman.com • Beds from Stickley to Mackintosh; Gustav Stickley bride’s trunk

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.