In Switzerland, cows are everywhere. Any plot of land larger than a cow, outside of the cities, is reasonably likely to be occupied by a few of this country’s ubiquitous dairy cattle. Their ever-present bells provide the soundtrack of rural Switzerland.

The true meaning of “alp” in Switzerland is not snow-covered mountain, but rather a mountainside pasture. The practice of sending cows to high pastures for the summer is known as l’alpage. It is in this tradition that we find the origin of the Swiss Chalet, a building with humble roots, which came to have significant influence on residential architecture in Western Europe and the United States.

The word “chalet” first appeared in Canton de Vaud in 1328 to describe simple log cabins, occupied by farmers during l’alpage—rudimentary shelters used for only a few months of the year. Seeing these ancient buildings today, not many people would think they fit our definition of “chalet.” That’s not surprising, since a lot changed over 700 years.

If a chalet is no longer the simplest alpine cabin, then what is it? At least two building types (besides the one described above) are classified as chalets. The first includes traditional wooden farm and rural structures particularly common in the Bernese Oberland section of Switzerland. They are primarily utilitarian, which is not to say unattractive. The second, more broadly accepted definition of “chalet” describes a type of in-town house that, though it did not originate in Switzerland, came for a long time to represent Swiss residential architecture to the world. According to Dr. Edwin Huwyler, director of the Swiss Open-Air Museum Ballenberg, this form had its genesis in the middle of the 19th century. It was created by French and English visitors to Switzerland who, after returning home, created romanticized, overly ornamented, and not particularly accurate versions of the vernacular houses they had seen.

As demand for these gingerbread houses increased, several Swiss companies began offering an early form of pre-fab housing: chalets from catalogs that allowed prospective owners to browse and select every form of kitsch to serve as trim. These houses appropriated the term, eventually replacing the traditional definition.

The footprint is typically compact, probably to minimize the amount of excavation required when building on steep terrain. The foundation is often stone or cement and is exposed on the downhill side. Copious windows and broad galleries (usually though not always present) serve to unite indoors and out, a critical function for a population enamored of outdoor activities. The galleries are bounded by a railing that caps vertical boards, closely spaced and sometimes decoratively carved. Window boxes, often planted with geraniums even to this day, offer an opportunity for color.

Viewing one of these houses in a mountain pasture, one need not wonder at Ruskin’s poetic description of them. Ruskin was quite contemptuous of the “Swiss” chalets sprouting up in the English countryside. He wrote: “Now, I am excessively sorry to inform the members of any respectable English family, who are making themselves uncomfortable in one of these ingenious conceptions, under the idea that they are living in a Swiss cottage, that they labor under a melancholy deception . . . ” One doubts that he was truly sorry to so inform his countrymen. Never one to shy from absolutes, he decreed: “It is not, however, a thing to be imitated; it is always, when out of its own country, incongruous.” Presumably, Ruskin would have had little sympathy for chalets in the United States. His opinion, not surprisingly, had no impact on their spread to America. The earliest chalet pattern books appeared here in the 1820s, predating Ruskin’s objections by roughly 70 years. It was not, however, until the booming post-Civil War economy that the chalet gained real traction in this country.

In disagreement with Ruskin, William Dana, in The Swiss Chalet Book (1913), wrote of the broad appeal and suitability of the chalet. “It is not Swiss; it is not Tyrolean, nor Himalayan. It is universal. And by reason of its inherent beauty it is adaptable to any site and any condition where land is plentiful, and where picturesqueness and harmony with the natural surroundings are the first consideration.” Even within Switzerland, the traditional chalet form was, and is, adapted for uses beyond the single-family home. One may serve as a public house or shop, for example, and it is not unusual to see overgrown chalets as hotels in mountain towns. This ability to scale well is an important distinction between chalets and their bungalow cousins.

The chalet was likely introduced to America by tastemaker A.J. Downing through his book The Architecture of Country Houses. Downing’s view of the chalet is more consistent with Ruskin’s: “The true site for a Swiss cottage is in a bold and mountainous country. . . or in a wild and picturesque valley. In such positions the architecture will have a spirit and meaning which will inspire every beholder with interest, while the same cottage built in a level country, amid smooth green field, would only appear affected and ridiculous.”

The earliest chalets built on this continent were typically summer or vacation houses. These early versions were among the most authentic ones built in the U.S., though American chalets were never literal copies. Even the 8,000-square-foot Gamble House by Greene & Greene, the brothers so associated with the California bungalow, was described by Dana as “a chalet in the Japanese style.” Some have speculated that the broad galleries common on chalets were precursors to the sleeping porches that became popular in California.

As with the chalet, the bungalow was disseminated via pattern books as well as articles in popular magazines and architectural journals. Clearly these early bungalows, as well as chalets, significantly influenced what came to be known as the American or Arts & Crafts bungalow. Numerous bungalow books identified houses as chalets. The primary difference is the inclusion of full second story in the chalet. As Giberti notes, the chalet form was not subsumed by the bungalow. The two styles coexisted or, perhaps, melded into a single type of country/suburban house.

Architects and critics distinguish buildings from architecture. Most of us spend our lives in buildings; Fallingwater and the Gamble House are architecture, which is to say art. These two advanced the field and altered public perception. They are deserving of acclaim, whereas a tract home is not. The distinction seems reasonable. By this same metric, chalets like those found at the Swiss Open-Air Museum Ballenberg would not qualify as architecture. What many of these structures represent, however, is the final perfection of a building type that sustained a way of life in often harsh conditions, a form that was exported to the world. There is, I think, something truly artful in that.

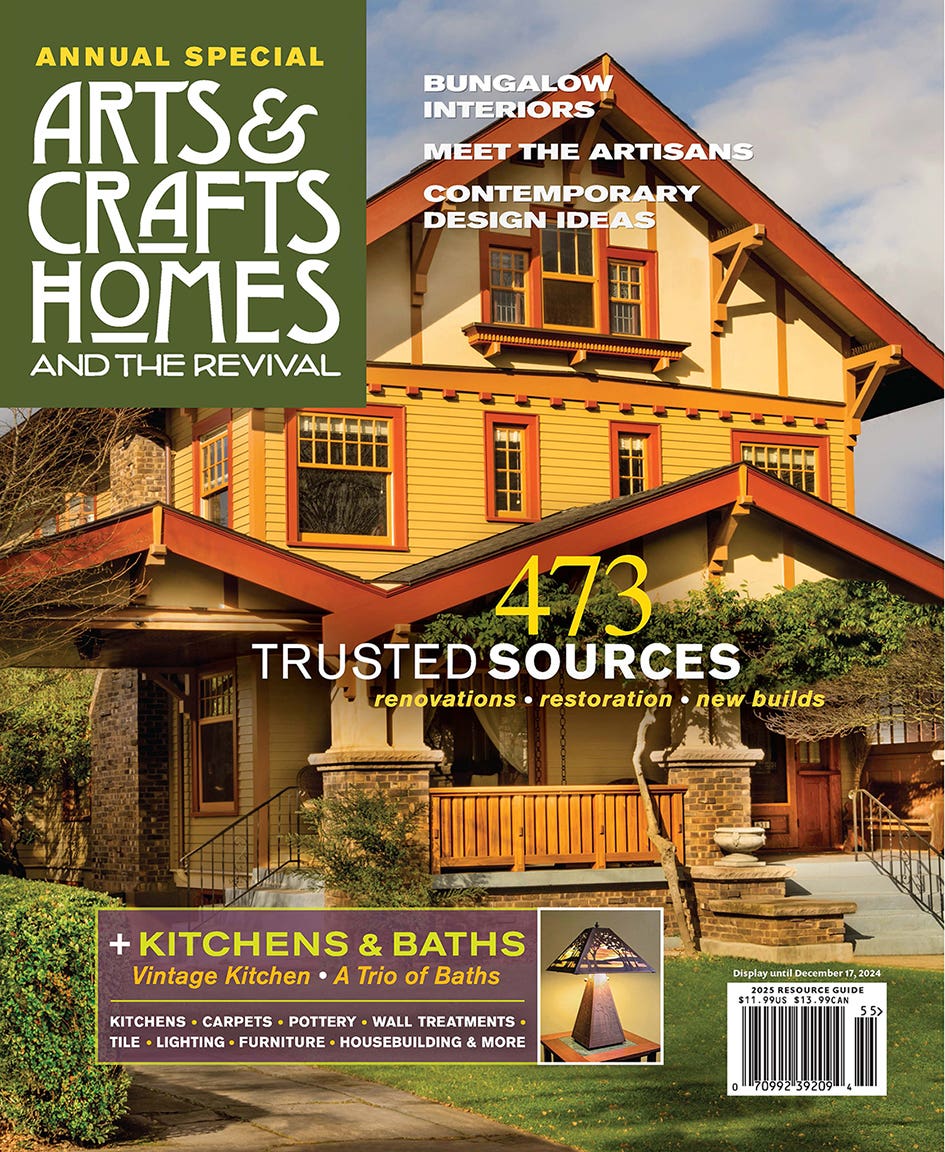

Arts & Crafts Homes and the Revival covers both the original movement and the ongoing revival, providing insight for restoration, kitchen renovation, updates, and new construction. Find sources for kitchen and bath, carpet, fine furniture and pottery, millwork, roofing, doors and windows, flooring, hardware and lighting. The Annual Resource Guide, with enhanced editorial chapters and beautiful photography, helps Arts & Crafts aficionados find the artisans and products to help them build, renovate, and decorate their bungalow, Craftsman, Prairie, Tudor Revival, or Arts & Crafts Revival home.