Two Arts & Crafts Kitchens: Bungalow Basic & Adirondack Spirit

White or rustic? Bungalow-era kitchens may be basic in white, while revival kitchens are new interpretations, often unique.

Two very different kitchens illustrate the wide range of design and materials that fit under the description “Arts & Crafts.” Both interpret design motifs ca. 1905–1930. The first—though it’s hardly plain—conjures up the basic bungalow kitchen with its subway tile and white-painted cabinets. The second, for a house newly built, is an artistic expression that marries Adirondack Rustic to Craftsman-era furniture details.

Kitchens of the Arts & Crafts revival are woodsy and filled with artisanry, but not so the utilitarian kitchens of the bungalow era. Cabinets were washable and renewable, painted in white enamel. Lighting was basic.

That look is beautifully interpreted today for practical kitchens that seem appropriate for any house. White subway tile and cabinets are timeless, relieved by the countertop in soapstone or wood. Stainless-steel appliances recall the nickel finishes of the period. In this kitchen, color is introduced through a bright yellow liner tile, painted fixture shades, and colorful dishware behind glass doors—as the butler’s pantry has come into the kitchen proper.

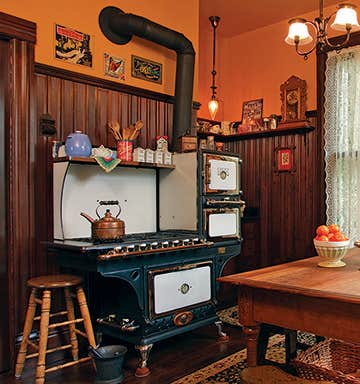

Adirondack-style Kitchen

The kitchen in a new Adirondack-style house brought the outdoors in—with tree trunks, a twig soffit detail, and landscape tiles. An asymmetrical design furthers the room’s naturalism. The owners liked the ruggedness of Adirondack style for their project in the Lakes Region of New Hampshire, but wanted more refined handcraft for elements such as cabinets.

Thus a Craftsman aesthetic is apparent in cabinets designed and built by Crown Point Cabinetry of inch-thick sapele finished in the company’s Nutmeg stain. The Arts & Crafts Designer series features crown moldings with brackets and tapered legs with faux tenons. (A mini-prep kitchen with small appliances sits off the main kitchen, with white-painted cabinets to lighten the windowless space.)

Painted in Crown Point’s ‘Lexington Green’ with a glazed finish, the island has the unfitted look of furniture. It is topped with Blue Australe granite. The stove is another focal point, with a copper hood and a colorful tile mural depicting (what else?) a wooded landscape.

The room divider is outfitted as a hutch on the kitchen side, with retractable doors to hide small appliances in upper cabinets that rest on the countertop. End panels have custom cutouts inspired by Arts & Crafts motifs, Frank Lloyd Wright’s in particular; marbleized opaque glass shows through, lending brightness.

All this detail is held in a rustic room featuring structural tree trunks that came from Maine. The soffit’s twigs are saplings cut in Maine and on the project manager’s forested property in New Hampshire. Beckwith Builders’ designer Aimee Bentley, AIA, explains the fabrication of the three-dimensional frieze: “Barked twigs were cut, sliced to length, and the backs shaved a bit so they would lie flat. Then they were applied to a plywood backing that had been painted black. The strips of plywood then were applied to the wall, and fir top and bottom trim routed to hold LED strip lighting.”

The unique house isn’t the first to draw connections between mountain rustic and Arts & Crafts design.

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.