Bungalow Windows

Bays and bump-outs, Prairie glass and diamond panes and cloud-lift muntins: artistic Arts & Crafts windows.

Unusual and occasionally even wacky, windows are a leitmotif of bungalows and other houses of the Arts & Crafts period. The vertical, six-over-one or two-over-two windows of earlier eras became the exception rather than the rule. One departure: A proportionally large, horizontal “picture window” can be found on many a small bungalow. A three-part window, with two narrower lights flanking a large center pane, is known as a Chicago window for its association with Prairie School houses. Sidelights beside the entry door may not extend to the floor. Different types of Arts & Crafts windows are found on a single house: a decorative oculus window in the gable, say, along with multi-light casements in the living room and standard double-hungs on the rear façade.

A “feature” window often occupies the main gable. Look for combination windows/vents, bump-outs and oriels, fanciful muntin patterns, and exaggerated trim. Bump-outs are also found in the kitchen (to grow herbs over the sink, perhaps), in the dining room (for a built-in settle), and in the living room (for extra light and display space).

Inglenook windows are an Arts & Crafts standard. These are the small, often square, windows that occupy the top of the wall over built-ins or benches that flank the fireplace. The flat windows found in shed dormers are sometimes referred to as “lie-on-stomach windows.”

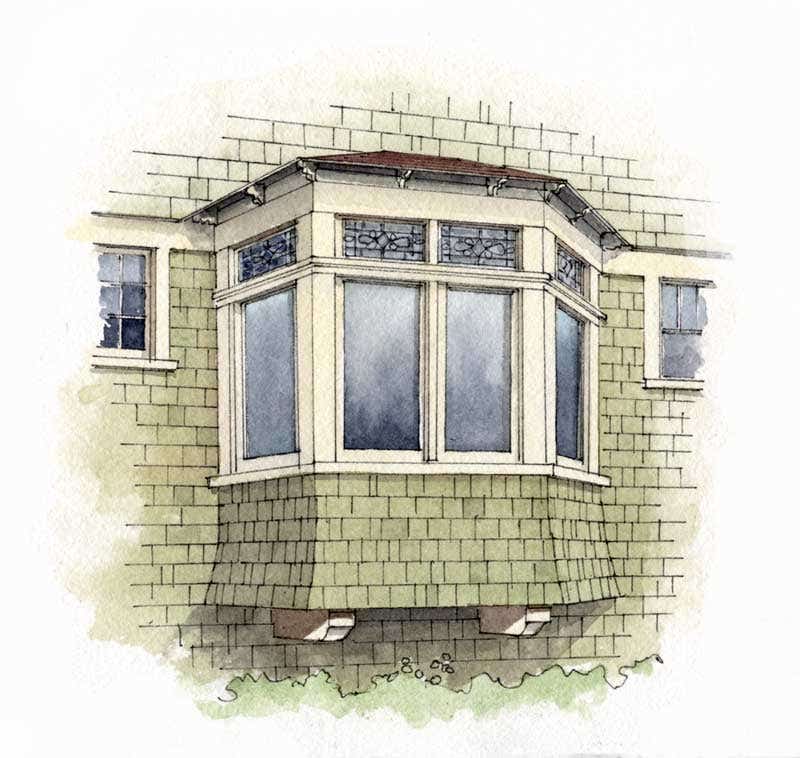

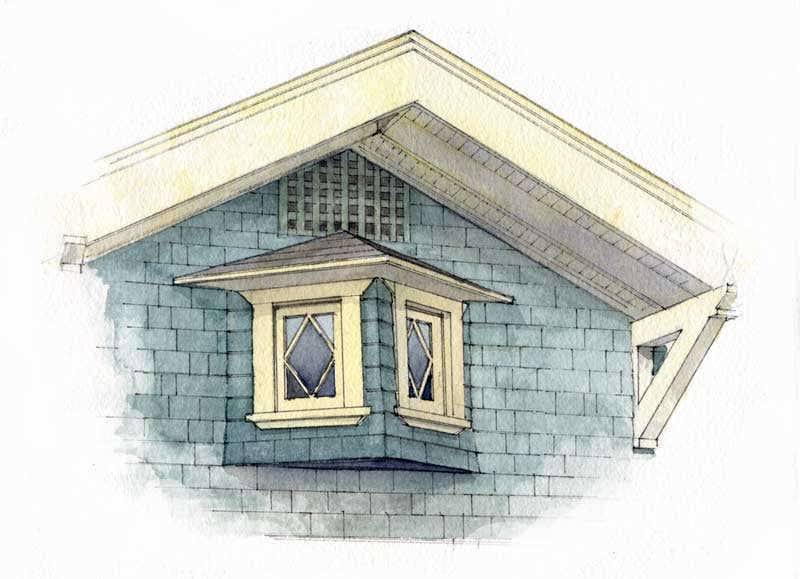

Bays and oriels made a comeback in this era—as a way to break the cube of an American Foursquare or to lend picturesque asymmetry to a Craftsman house. (A bay may be round or faceted; an oriel is window, often carried on brackets and corbels, which projects from the wall but doesn’t extend to the ground.) The projecting windows may be embellished with transoms, art glass, or fancy muntin patterns. Over-scaled corbels or knee braces provide visual and structural support.

Windows act as a key to other styles of the era. Tudors and English Arts & Crafts houses have diamond-pane windows or decorative medallions in casements. Chicago bungalows famously sport Prairie art glass in geometric designs.

Window proportions changed in this era, often with beautiful results. A horizontal window or transom over a large pane has architectural interest, and it’s practical—only the lower section needs to curtained for privacy. Which brings up the subject of window dressings in the bungalow era: They’re simple, or nonexistent. Curtains are not necessary to cover small windows high in the wall, or Prairie-glass casements, or small diamond panes. Simple treatments are appropriate even on larger windows, and include panels hung on a rod from rings, roller shades, and interior shutters.

Arts & Crafts Windows: Bump Outs, Oriels & Bays

Walk, don’t drive, around a bungalow or Craftsman neighborhood, and you’ll see them: strange little windows that stick out of a side wall or a gable or into the porch. They provide exterior interest on what might otherwise be a small or plain house. Inside, these bump-outs contribute to the nooks and built-ins so beloved in bungalows and other artistic homes of the era. Sometimes the bump-out or oriel is simply an excuse for a feature window (or three). Details can be combined in an infinite number of variants.

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.