Arts & Crafts Style: A House Remade

A renowned Vermont architect with a broad resume interprets the Arts & Crafts way of building—especially apt in this region rife with artist–craftspeople.

The best street in this New Hampshire town is lined with authentic colonials, some look-alikes painted white, a Shingle-style house or two. But it was a 1940s “fake two-story colonial” that the clients chose, because it backed up to a community pond, and because its badly remodeled rooms allowed them to indulge their desire to create an Arts & Crafts interior.

Architect Dave Sellers was skeptical. “It was chopped up into small rooms, with little relationship to the outside. A small greenhouse out front was cocked off at an angle and in shadow most of the day. It was a toss-up whether to tear the house down. (We ended up taking it back to the joists, and they had to be sistered.) But we decided to keep the shell…I like to recycle rather than throw it all away.”

Dave Sellers graduated from the Yale School of Architecture in the same class as Thomas Beeby, Allan Greenberg, and Robert A.M. Stern. He was named one of the world’s 100 foremost architects by Architectural Digest in 1992. His career has been unorthodox; he does what interests him most. These clients wanted Sellers, and they also wanted Arts & Crafts. Another path to explore: Sellers was on board.

“I love the tradition,” he says now. “I’ve studied Greene and Greene and early Wright, Mackintosh, others. In the past I’ve referred to the revival as Bungalow Joy. So I said, Let’s go!” Intuitively, he set to finding the right craftspeople and the most suitable materials, beginning relationships that would have him working beside artisans, sketching details in their shops.

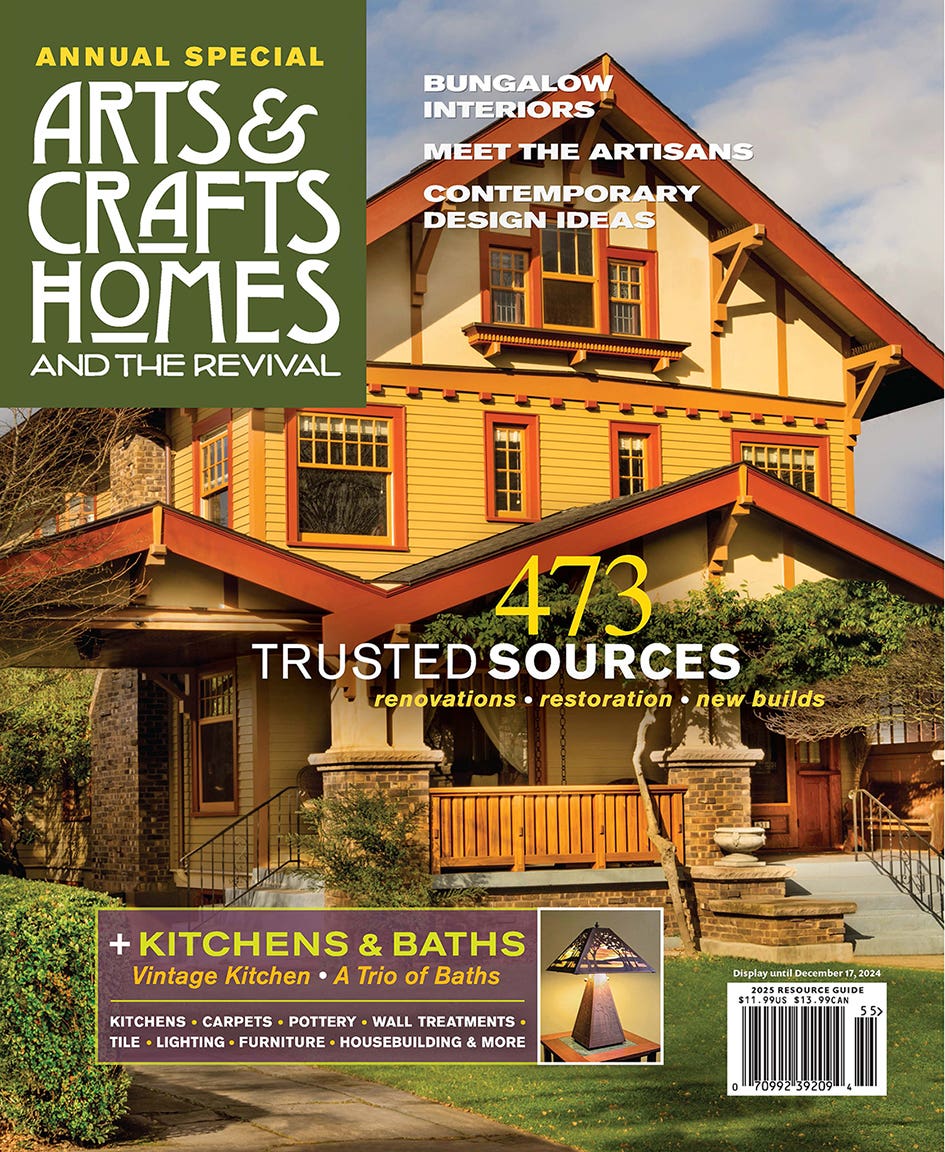

The owners have a small but very nice collection: Joseph Hoffman Secessionist chairs, good silver, and European antiques from the A&C and Deco periods. All of it fits well in the interpretive new interior. The white-clapboard façade blends into the neighborhood, belying the surprise just inside. “I used the entry portico to announce [our vision], and then I went full bore into my idea of A&C on the interior,” Sellers explains.

“I love architectural details and the hand crafts I associate with Architecture, not just Arts & Crafts. So I took this opportunity to design it all: critical light fixtures, the trim, all the built-in furniture, stairs and railings, flooring. A fine New England craftsman, Peter Brough, was contracted exclusively for all the doors, cherry beams and columns, and built-ins.” Another surprise is a secret door built into the basement’s library. “All you have to do is rotate Moby Dick a little, and the door swings open to the buried wine cellar,” says Sellers, grinning.

Sellers is a fan of traditional mortise-and-tenon joinery, but sympathizes with the visible expression of joinery in unique A&C vocabulary. He asked Brough to cut a square hole at the top of doors to expose half the tenon end, then set in a square of art glass with enough transparency to see the joint. For the custom-made light fixtures, he looked to California’s Greene and Greene rather than to Wright’s Prairie designs or Mackintosh’s Art Nouveau vocabulary. A local glass artist made the art glass from full-size patterns, which was installed in cherry frames made in Sellers’ own shop.

The homeowners are plant collectors, as well as people who appreciate an interior awash in daylight. The architect specified a greenhouse addition, this time on the lake side. Artist–masons from Pharaoh Stone in Warren, Vermont, put together the walls under the greenhouse, as well as at entries and in the gardens, with skill and “an understanding of local rocks and how they fit together,” Sellers marvels.

David Sellers: architect, inventor, heretic

The description for a course led by Dave Sellers identifies him as “architect, inventor, holder of several patents, designer of windmills, stoves, furniture, light fixtures, trains, sports products, etc.” One might add tilter at windmills; Sellers is the designer working with utopian physician Patch Adams at his Gesundheit Institute in West Virginia. Dave has used found materials (most famously with 1970s Vermont’s Prickly Mountain enclave), worked in sustainable architecture and planning, embraced the vernacular, designed an airport and a gym, been architect for New York’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine, contributed to a weird, elite vacation resort in Connecticut, and designed products including the Z chair and a dome. Look at his residential work and find hints of Adirondack camp, the early modern Ranch, and machine-age sensibility. For this project, Dave Sellers embraced Arts & Crafts.

“All of the ‘styles’ I’m aware of have in common a respect for materials, and the craft of assembling them to create pleasing scale, proportion, and continuity—it doesn’t matter what the vision is.

“ I don’t seek out this kind of design problem,” Dave says, referring to clients with a vision and a stomach for details. “But when the owners truly see the value of the investment . . . . It takes a client who says ‘I want this, and I want the best you can do’.

Sources

• ARCHITECT David Sellers, Sellers and Company Architects, Warren, VT: sellersandcompany.com, 802/496-2787

• Associate designer Lourie Savage, Warren, VT: 802/496-4383

• STONE MASONS Pharaoh Stone, Warren, VT: 802/496-7120

• CABINETMAKER Peter Brough, East Calais, VT: 802/456-7440

• TILE in the style of Batchelder by Tile Restoration Center, Seattle: tilerestorationcenter.com, 206/633-4866

• WALLPAPER by Morris & Co.: william-morris.co.uk

• Furniture is antique.

• KITCHEN CABINETS in cherry by Richard Bissell, Putney, VT: Richard Bissell Fine Woodworking, bissellwoodworking.com, 802/387-4416

• GREENHOUSE fabricated by Marston & Langinger, London, UK: marston-and-langinger.com

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.