English and American Traditions in a New Craftsman Home

An enlightened architect’s interpretation of British Arts & Crafts precedents, for a house in New Jersey.

Photos by Bruce Buck

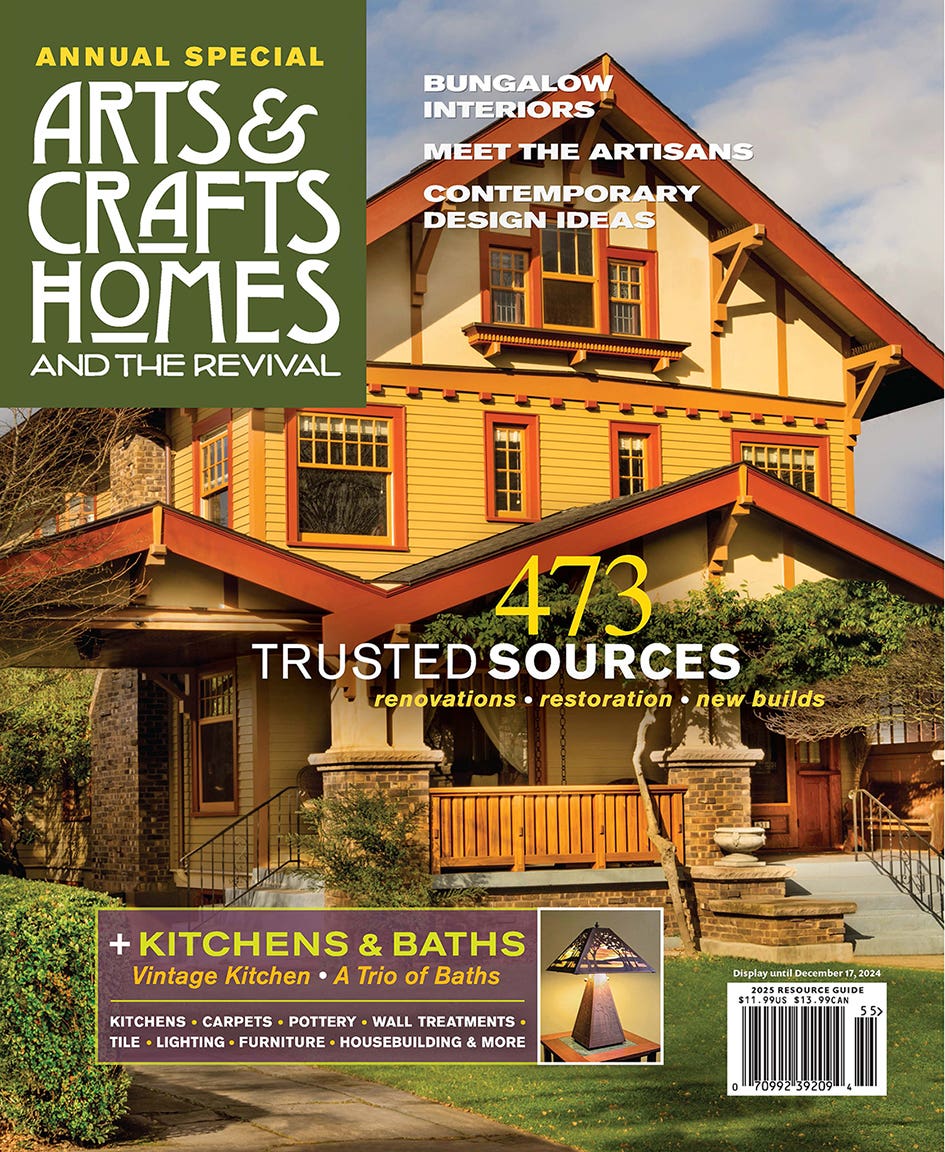

Architect Ed Heinle, who is a trustee and vice president of the Craftsman Farms Foundation (the Stickley museum in New Jersey) and a regular attendee of the Arts & Crafts Conference at the Grove Park Inn in Asheville, likes to talk about this project. “You approach the property along a straight, rising country lane. When the house suddenly comes into view, it’s a favorite moment—because it all looks inevitable.”

Harold and Martha Wrede gravitated towards Arts & Crafts design in the 1990s as they contemplated building their retirement home. Their program at first called for just one level. Under Ed Heinle’s direction, it developed into a more space-efficient two-story design, but with the main living area all on the first floor. The second level is essentially a guest floor. The Wredes coveted wood paneling and wainscoting in rooms decorated without fuss. They were not interested in a reproduction house; hence a design that newly interprets various influences.

“Though I wouldn’t say the house is intentionally British,” Heinle explains, “my appreciation for and long study of Lutyens, Voysey, and Mackintosh meant their influence was bound to emerge. And I was a student of Robert A.M. Stern at Columbia—Bob opened my eyes to the great American Shingle Style.”

paint colors, interior design, and furnishing were collaborative. “We would meet at a great little country inn nearby,” Heinle says, “where we dined outdoors over paint fan-decks and brochures. Wine eased the process.” The owners chose many of the appointments after construction, but they consulted their architect for his opinions on suitability. All along, the relationship was a good one.

“I don’t care for architecture that struggles to be ingratiating,” Heinle continues. “This house has a certain dignity—a sober elegance and reserve when it’s first approached, which becomes a rich welcome as you pass through the door. I like to think it reflects my clients.”

The soaring great room is well proportioned—“not a soaring Sheetrock box,” as Heinle puts it. The kitchen is convenient to and visible from the great room, thus the use of white oak for cabinets. Both the American and British movements—and their revivals—are represented: There’s a birch-tree paper frieze from California, a new desk after Frank Lloyd Wright, an antique tall-case clock of Koloman Moser School (Vienna) design mixed with reissued and interpretive pieces by Stickley. The mantel in the great room holds Fulper pots from the early 1900s, antique Meissen porcelain, a Loetz glass bowl of ca. 1901–03, and Grueby reproduction pots, all arranged beneath the copper charger in Stickley seedpod motif, done by contemporary Roycroft artisan Robert Trout. Navajo rugs share space with reproduction rugs from Stickley and textiles from Archive Edition.

The couple have in mind a garden gazebo (already designed). “Once we thought that the property should be left in its natural ‘woodsy’ state,” Harold Wrede says. “After the house was built and we could better visualize its setting, our garden and landscaping genes took charge. Now we have the biggest garden we’ve ever had.” And Harold wants a room devoted to model trains, a hobby of his when he was young.

“The house has a palpable presence that’s hard to describe—a quiet mystery, like a piece of art pottery or Gustav Stickley’s early furniture,” says Heinle. “But my favorite thing about the house is that I’m still welcome there. Which is not always the case between architects and clients!”

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.