A Painterly Approach To A Prairie-Style House

A fine artist and his wife took a hands-on attitude to bring back a picturesque Prairie-style house on a Minnesota lake.

Born and raised in St. Louis Park, a historic neighborhood in Minneapolis, Malcolm “Skip” Liepke had an artist’s eye even as a child. He went on to become an internationally recognized painter. (His paintings have been on the covers on Time and Newsweek, and hang in the Smithsonian.) Influenced by Impressionists including Whistler and Degas, his work celebrates poignant and intimate moments, often ones of sensual pleasure.

When Skip and his wife, Michelle, moved back to Minneapolis in 1990 to search for a residence in their hometown, it’s no surprise that they focused on warmth and intimacy, light and color. Skip wanted a home filled with character and charm, a house with inviting colors, a refuge from the cold icy whiteness of Minnesota’s long winters.

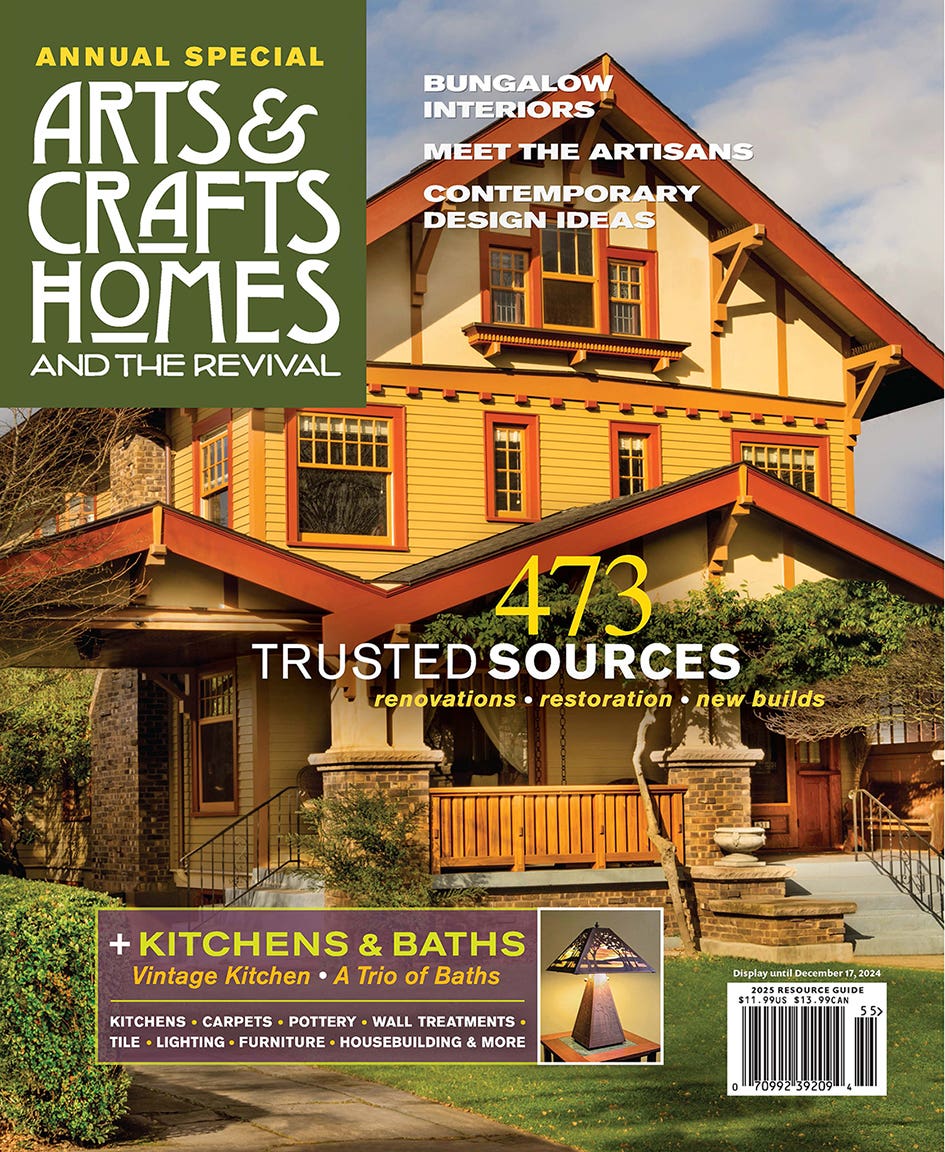

The couple knew immediately that this Prairie-style house was what they were looking for. It’s perched on a gentle rise above Lake of the Isles, a scenic, 109-acre lake created from marshland in the early 20th century. The 1915 house was solidly constructed and has details that show the hand of the craftsman. It evokes Japanese design—a source of artistic inspiration for Skip—in its horizontal emphasis, flowing interior space, extensive use of woodwork, and ornamental restraint. A hipped roof with broad eaves sheltering bands of windows helps the house blend into its setting.

The house had deteriorated: Leaded-glass windows were cracked and sagging; modern wrought-iron screens covered windows, obscuring lake views; interiors were painted in a restless pink; and hardwood floors were hidden under mint-green carpeting that had seen better days. The kitchen was dark and inefficient; a warren of cramped bedrooms awaited improvement upstairs. Outside, the stucco needed redoing but the clay tile roofing was intact.

With a painterly eye, Skip was hands-on, guiding every aspect of the restoration. He refinished all of the woodwork, custom-mixed paint colors, and designed the new kitchen wing. Now twice the size of the old kitchen, the space is light-filled and welcoming. It is compatible with the rest of the house, but Skip admits that it has more color and panache than a period kitchen might have had. Inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, Skip designed a band of colorful, geometric transoms that encircle the room, lending extra brightness even on gloomy winter days. Mahogany cabinets are accented with rectilinear, hand-carved detailing echoed in a box-beam ceiling.

Skip refinished the poplar woodwork in the living and dining rooms and in the enclosed front porch. After he cleaned it, Skip learned to restain it in the original mahogany color—a process complicated by the tight grain of the old-growth wood. Walls in the living room, hall, and stairwell got seven layers of taupe-colored Venetian plaster. Other rooms are in a fall palette, all the colors mixed by the artist: olive green in some rooms, autumnal gold with burgundy accents elsewhere. At the back is a garden room that was added in the 1920s; connected to the kitchen addition, this became a family entertainment room. Upstairs, bedrooms were reconfigured into a master suite and three children’s rooms. The bath room, capriciously updated at some point with pink tiles, was remodeled for the period of the house.

The house is furnished with Japanese pieces and Prairie School antiques. Highlights include a Stickley oak dining set, a Japanese tansu chest (displaying woven baskets, block prints, and ancient pots), Secessionist silver, and a prized Mackintosh mirror from Glasgow’s Willow Tea Room.

Minnesotans will tell you that home maintenance is constant. Projects for the Liepke family this year include replacing plants that died during last year’s fierce winter, and repainting exterior trim damaged by ice. Still, with its Japanese sense of balance, the Midwestern house is a warm refuge.

Brian D. Coleman, M.D., is the West Coast editor for Arts & Crafts Homes and Old House Journal magazines, our foremost scout and stylist, and has authored over 20 books on home design.