A Sunny 1906 House in Portland

Once derelict, a 1906 house in Portland is faithfully restored, then decorated with rich colors and a mix of vintage and revival furniture, textiles, and pottery.

A piano started it all. Happily settled in a 1908 Foursquare in Portland, Oregon, Jim Heuer and Robert Mercer weren’t planning on moving. Then Jim bought a big, antique piano—a Chickering square grand built in 1871. It didn’t fit in the parlor and took up a bedroom upstairs. So began the hunt for a house with a big living room; the partners wanted a vintage house with character, preferably in the Irvington area of Portland.

Their agent brought them to this stucco house on a tree-lined corner; they viewed it on a dark, rainy afternoon in 1999. The exterior was a dirty pink with peeling green trim. Rooms showed dark, only partly because the electrical service was down. Walls were in bad shape. The windows, actually one of the best features of the house, were hidden behind layers of vinyl “lace” that had mildewed. (Pulling the panels aside revealed broken panes covered with cardboard cut from cereal boxes.) The pantry wainscot of Douglas fir was covered in layers of floral wallpapers, and the kitchen had gotten a cheap update that included shiny black-and-white countertops. In the attic, another broken window attracted the pigeons that were roosting inside.

Showing great imagination, the partners thought the house intriguing. They recognized that casement windows throughout let in a good deal of daylight. Original tongue-and-groove paneling was visible behind peeling wallpaper in the breakfast room.

In other rooms, original woodwork of Douglas fir had not been painted, though the varnish had darkened. On the second floor, the master bedroom was nearly as large as the living room and had a romantic fireplace. The living room, which ran the entire width of the front of the house, had plenty of room for the piano. They made an offer the next day.

The 1906 house was designed by Portland architect Emil Schacht, as the reverse duplicate of the “ultra modern showhouse” built just across the river for the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, a World’s Fair that drew over two million visitors.

In their research, Jim and Robert found that their home had been “updated” in the 1920s; stucco was applied over the wood-shingle siding, and much of the living room’s woodwork was removed.

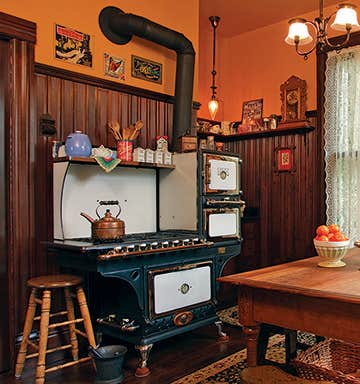

The basics came first: a new furnace and water heater; copper and PVC to replace clogged iron water pipes. Electrical service was brought up to code and gas fireplaces rebuilt for safety. In the breakfast room, composition wainscoting covered in seven layers of peeling paper was torn away to reveal the century-old tongue-and-groove boards on walls and ceiling. Restoring the breakfast room taught the partners two things: that the house had gorgeous woodwork well worth saving…and that they did not have the energy to strip and restore any more of it themselves.

They relied on the expertise of preservation architect Chris Cooksy and general contractor Craftsman Design and Renovation to bring back the living and dining rooms. Old-growth Douglas fir salvaged from an industrial water tank was used for patching. To replace missing fir plywood in the stair landing, they sanded down plywood rescued from a 1930s kitchen. (Plywood faced in Douglas fir was a “modern invention” when the house was built, first produced for the Lewis and Clark Exposition.)

Woodwork was restored by way of 50+ gallons of furniture refinisher, used to remove the crusty alligatored finish. A master colorist came in to stain wood, matching newly cut fir, salvaged plywood, and the original woodwork. Then multiple layers of orange shellac were applied, bringing back the glow.

Windows were rehabilitated, not replaced: Out came all 348 lights (glass panes). After the sashes were stripped, they were reglazed with the original glass, and weather stripping was added in newly cut rabbets. In lieu of aluminum storms, a custom-fitted, wood-framed storm panel was mounted on the outside of each casement. The now-efficient windows open normally and meet State Historic Preservation Office standards. All the hinges and latches also were removed to be cleaned and replated with an oiled-bronze finish closely resembling the original. Window repair was labor-intensive, but the cost of the entire process was about half that of replacement with good double-glazed windows. And character is intact.

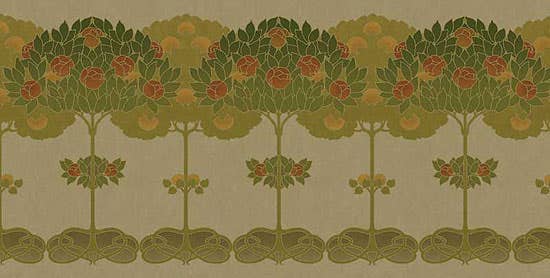

Arts & Crafts furniture, both antique and reproduction, then began to fill the rooms. Near the living-room fireplace, a capacious Morris chair (Lifetime Furniture, ca. 1912) sits near a small reproduction rocker and an armchair by L. and J.G. Stickley. Portland furniture craftsman Walt Heck made the quarter-sawn oak dining table based on designs from a vintage Limbert catalog. The master bedroom is furnished with locally made furniture in cherry with a simple oil finish.

The sunny, bold colors of Italian pottery cued some of the paint colors in the house. Robert’s grandmother, Almerinda Gallicchio, emigrated from Italy to Portland in the 1950s—and Jim and Robert have made frequent trips back to renew family ties in the old country. They have been collecting colorful majolica from Deruta in Umbria, Siena in Tuscany. These pieces are a reminder of summers spent under the Italian sun; they add a personal note to the interior. Vintage and contemporary American pottery, including Native American work, also adds color.

Brian D. Coleman, M.D., is the West Coast editor for Arts & Crafts Homes and Old House Journal magazines, our foremost scout and stylist, and has authored over 20 books on home design.