Evolution of the Morris Chair

Learn about the history of the Morris Chair—the first recliner. A staple of Arts & Crafts furniture lines, the adjustable-back Morris chair actually dates to 1865 and William Morris’s English firm.

Early History of the Morris Chair

It was three years after the founding of the firm of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. in London. Success had come quickly and by 1865 the firm had several new members, among them business manager Warrington Taylor. While visiting a number of small cabinet shops in Sussex that year, Warrington came across a chair that intrigued him. He made a quick sketch of the design and sent it along to the firm’s chief designer, architect Phillip Webb. With a few modifications by Webb, the chair was put into production and the reclining chair—ever since known as the Morris chair—was born.

It remained a staple in the Morris & Co. line until the firm closed it doors in 1940. Within years of that first chair, dozens if not hundreds of versions of the Morris chair were being produced in factories and small shops from Vienna to San Francisco.

A Comfortable Construction

All Morris chairs have an adjustable back, a detail that is highly adaptable to almost any design vocabulary. Then, Morris chairs are, quite simply, comfortable.

They are comfortable because they are cushioned . . . all of them. For the sake of clarity and design study, a Morris chair is often photographed partially clothed, that is, with the back cushion removed (or even naked, with no cushions). But from the beginning, seat and back cushions were standard.

Morris Chairs in the Arts & Crafts Era

Early in the 20th century, every Arts & Crafts furniture manufacturer worth his salt had his catalog peppered with Morris chair variations. There were bow-armed, flat-armed, and slant-armed models, even cushioned-armed versions, but never an un-armed version. The stylistic influences ranged from Jugendstil, as in some of the American maker Charles Limbert’s designs, to Prairie School, as in the box-like forms of both Frank Lloyd Wright and Purcell & Elmslie. There were hybrid forms that combined Gustav Stickley’s slatted Craftsman style with the Prairie versions to produce the very popular and frequently copied spindle forms.

With a few exceptions, the Morris chair in the United States tended to reflect the national personality—sturdy, reliable, predictable, and unsophisticated. The same chair, as it evolved in England and Europe, tended to be delicate and highly variable, as if always self-conscious of its own styling.

The American Morris chair, coast to coast, could be found made of any of the commonly used woods of the day, though it was and still is most frequently rendered in quarter-sawn white oak. The chair cushions were available in a wide variety of leather colors and textile patterns. It is interesting to note that Morris chairs in England and on the Continent seemed to have evolved exclusively with fabric cushions. I have yet to spot a Morris chair in leather from across the Atlantic.

The reclining mechanism is strictly low-tech—with none of the complex levers, springs, or on-board sensors of the La-Z-Boy recliner. The back is simply hinged where it meets the seat bottom and supported from behind where it meets the arms, either by a continuous bar or by two pegs inserted into holes in the arms. The reclinee was thereby required to get a minimum amount of healthy exercise by getting out of the chair and perambulating around to the back to make adjustments.

Two Extreme Designs

Two of my own favorite Morris chair designs represent the extremes to which this form was taken---extremes not just of design and appearance but also of the methods and philosophy of work.

One chair, designed by William Price, was built entirely by skilled craftsmen in the small furniture shop that was part of the Rose Valley Community outside of Philadelphia.

The formal styling of Price’s design vocabulary required considerable handwork and knowledge of the cabinetmaker’s trade. The back adjusting mechanism was clever and different. Rather than the back pivoting from a point where it was hinged to a fixed seat bottom, the back was fixed where it met the arms. The seat bottom was not fixed but rested on a frame and, when pulled forward, would cause the back to pivot or recline. This did eliminate the possibility of any exercise but, since none of Price’s chairs ever were put into production on any scale, their lazy-boy design did little to damage the gene pool.

The other extreme chair is the “Sitzmachine” by the Viennese designer Josef Hoffmann. He had no aversion to using machines to do what they did best, which was to make identical parts with great precision. (Like Morris, Hoffmann was opposed to using machines to mimic handwork.) Machine technology opened up possibilities . . . with thoughtful design, standardized machine-made parts could also double as decorative elements. The “Sitzmachine” is a perfect example of how machinery, once wildly misdirected, could be, finally, under the guiding control of the designer–craftsman.

Kevin P. Rodel lives in Maine, where he usually builds furniture, and occasionally teaches and writes.

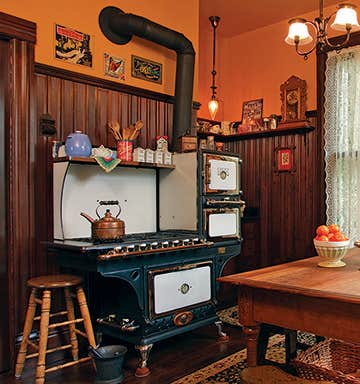

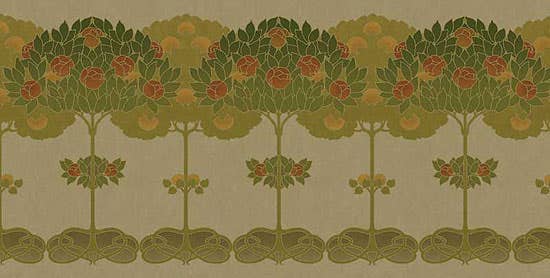

Arts & Crafts Homes and the Revival covers both the original movement and the ongoing revival, providing insight for restoration, kitchen renovation, updates, and new construction. Find sources for kitchen and bath, carpet, fine furniture and pottery, millwork, roofing, doors and windows, flooring, hardware and lighting. The Annual Resource Guide, with enhanced editorial chapters and beautiful photography, helps Arts & Crafts aficionados find the artisans and products to help them build, renovate, and decorate their bungalow, Craftsman, Prairie, Tudor Revival, or Arts & Crafts Revival home.