Fumed Oak & Wood Stains

Anyone with the bug for Arts & Crafts furniture discovers the look and lore of fumed oak—but did you know there’s much more to Arts & Crafts wood finishes than chocolatey brown?

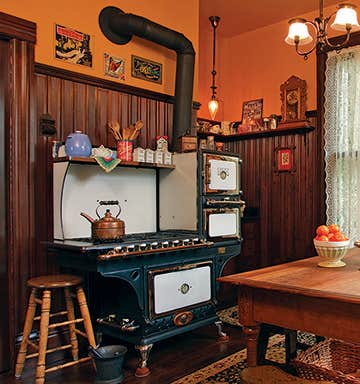

Perhaps you’ve heard that Gustav Stickley spent his later years like an alchemist experimenting with chemicals in search of new wood stains and colors? It’s true. Ammonia-fumed oak has always enjoyed the spotlight as the signature finish of the Arts & Crafts era, particularly for Stickley’s furniture and woodwork, but despite the Craftsman hype, this method was far from unique at the time, as Stickley himself acknowledged.

Chemical colors Ammonia-finishing is, in fact, just one of a group of techniques once known as chemical water stains, which capitalize on the ways different woods react when they come in contact with acids or bases. Chemical water staining is time-consuming and was therefore abandoned by manufacturers by the 1940s in favor of easier-to-use aniline dyes. However, the techniques have always been respected for their durability, color penetration, and the way they enhance the beauty of wood without obscuring its grain.

Ammonia-on-oak As many Arts & Crafts devotees know, the fumed oak finish at the center of the Craftsman canon is produced by enclosing white-oak boards in a sealed container or paper tent, then exposing them to the fumes of strong ammonia placed in bowls on the floor. The fumes react with the high concentration of tannins present in oak, turning them to the warm, chestnut brown admired by Arts & Crafts designers because it evokes the deep, antique color of ancient English furniture. Since ammonia fuming is not merely a dye applied to the surface, but a conversion of the wood that penetrates several millimeters into its fiber, the effect is not only very scratch-resistant, but it also continues to mellow with time.

Stickley lays the origins of the technique to a happy accident where boards left in an English horse barn were found to mellowed to brown. While Stickley does not assert he discovered the ammonia effect, he does stake a claim on the fuming process, saying “to the best of our belief, it was not discovered until the experiments with fuming made in The Craftsman Workshops.” The fact is, though, brushing ammonia solutions directly on oak was a well-known darkening method by the late 19th century; the the fuming technique using bowls of ammonia (which produced a mellower and more uniform tone) was published in America as early as 1895 in The Hardwood Finisher.

Ammonia-on-chestnut What gets overlooked today in our fawning over fumed oak is that, depending upon tannin content, ammonia also works magic on many other wood species. Stickley himself noted that “chestnut takes ever more kindly than oak to the fuming process.” Though he advocated chestnut as second only to oak for interiors, Stickley thought fuming the already rich wood was overkill “… unless a deep tone of brown is desired.” Modern artisans and conservators who have tried their hand at these techniques find that while chestnut can indeed go very dark with ammonia, if handled carefully (with light applications and follow-up treatments) it produces very pleasing results.

Sulphuric acid-on-birch One of the most dramatic chemical stains is the action of sulphuric acid on birch, which, depending upon the concentration, can turn this pale blonde to pinkish wood a rich mahogany red. Stickley particularly likes this treatment for red birch, which “gives it a mellowness that is as fine in its way as … oak or chestnut fuming” and is “desirable for woodwork in rooms where light colors and dainty furnishings are used.” For the record, period texts also cite the same effect by applying nitric acid on birch or cherry.

Sulphuric acid-on-cypress No surprise, Stickley liked how the Japanese treat cypress to a “soft grey-brown” that contrasts with the wood’s markings. This look is obtained in the Orient, he says, by temporarily burying the wood, but his alternative is to brush the wood with a dilute solution of sulphuric acid in a room at least 75 degrees F. Stickley also advises that sulphuric acid has a similar effect on hard pine, but he notes that such effort might as well be spent on a more interesting wood.

Acetic acid solution-on-maple An unlikely yet widely used chemical stain is a solution of iron in acetic acid. Stickley recommends it on maple to bring out a clear, silver-grey finish, and says to make the mix by letting nails or iron filings soak in acetic acid for a week, then draining off and diluting the liquid. Long before Stickley, variations on this concoction were advocated as a silver-grey dye for hardwoods; the method called for filling an iron kettle with old iron nails, hoops, and even gun-barrel borings, allowing them to rust, and then boiling them in one gallon of vinegar and two gallons of water. Modern experimenters report that soaking steel wool in vinegar is an easy way to make this “nail juice” that, besides being non-noxious, does indeed turn maple a beautiful silvery color that can be enhanced with aniline dye.

Stickley and earlier authors always advised testing chemical stains first to judge results, and working carefully with these potentially dangerous acids and bases, wise counsel today. Stickley generally recommended a light shellac coat on fumed oak furniture to protect it from wear, but interior woodwork needed only a coat of prepared floor wax rubbed to a satin finish. In the view of a noted Arts & Crafts conservator, “just fuming and waxing was a pretty radical departure” from the complex and varnished finishes common at the turn of the century. In this light, his finish techniques are among his lasting contributions to the Arts & Crafts Movement.

Related Products:

Gordon H. Bock, Assoc. AIA, the former longtime editor of Old-House Journal, is a contributing editor at Traditional Building magazine, co-author of The Vintage House, and a writer/editor for many architectural periodicals and books. An instructor with the National Preservation Institute and the historic preservation program at Drew University (1997-2016), he travels widely giving keynote speeches and professional seminars and as a technical and architectural consultant.

The hidden pen behind some popular names, Gordon is a national expert in architectural content as well as a communications professional. With a MS in Publishing, he has over 25 years of experience managing and developing in-house publications, magazines, online extensions, and related franchise media. For more information, contact Gordon at ghbock@comcast.net.