Aladdin’s Magic

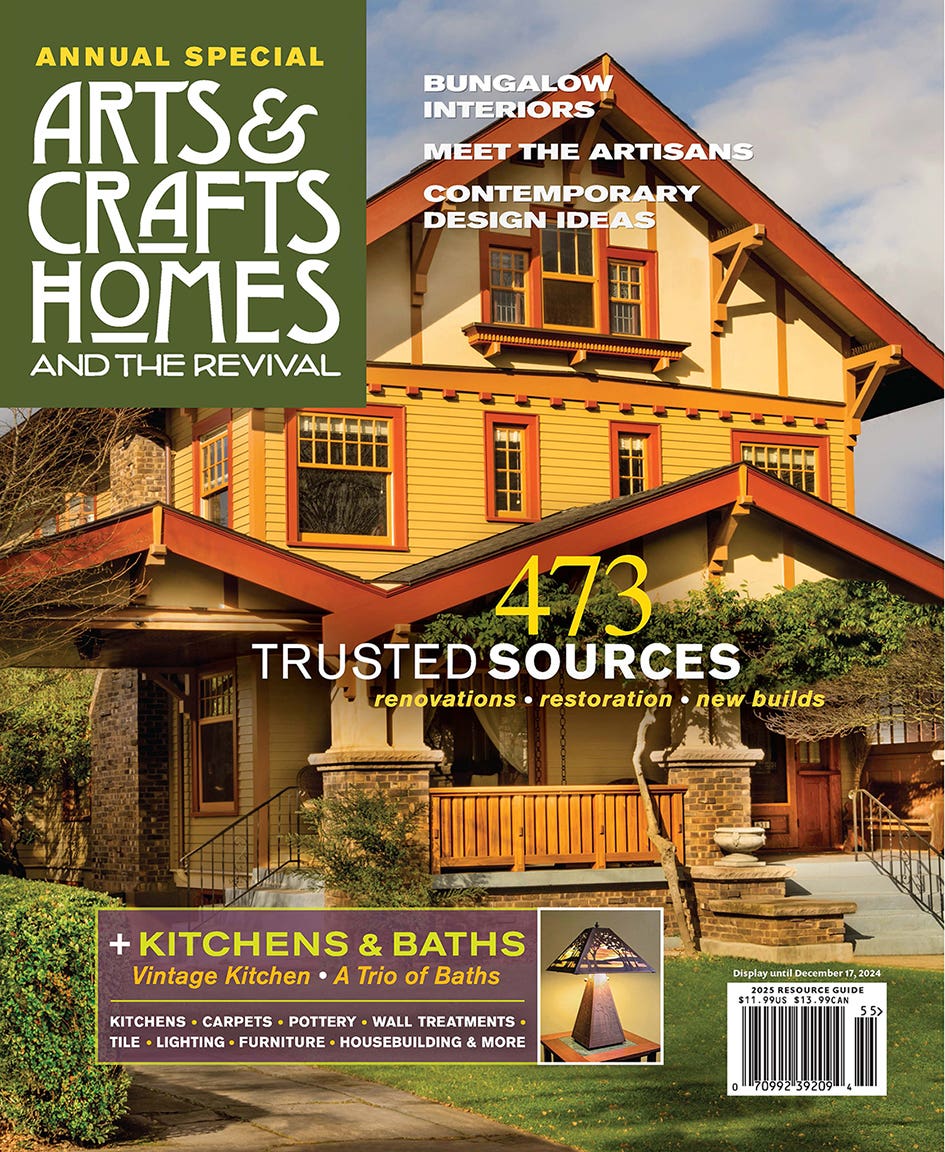

An unusually handsome model with English pedigree, “The Rossley” pre-cut home by Aladdin has great character.

Given that this is Bay City, it’s not surprising that homes by the Aladdin Company are around every corner. Aladdin, which sold and shipped pre-cut house kits labeled for assembly, was founded in this Michigan city, an old lumber town, in 1906. It was started by brothers William and Otto Sovereign, the company remained solvent and family-owned until it shut its doors for the last time in 1981. “There are hundreds of Aladdins here,” says Todd, who has lived in this model for many years with his wife, Ann, and their kids, Olivia and Caden.

The couple had their eyes on this house for a while. “We’d been collecting American Arts & Crafts furniture for years,” Todd explains. “Our previous house, about six blocks away, was nothing special. We’d walk past this one at night so we could peer in through the big windows and try to figure out the floor plan.

“We even told the owners we’d love to buy their house someday, but they insisted they would retire here and stay. Eighteen months later they put it on the market—without calling us! We were the second family to tour…immediately we put down good-faith money and we got it.”

Ann and Todd knew it was an Aladdin house, and soon learned more from their friend, the local historian and Aladdin expert Dale Wolicki. “The Rossley” was built in 1914–15 and appeared in Aladdin’s 1916 catalog, but not in subsequent editions. The second-most expensive kit house in the catalog, it leaned toward avant-garde English work. “Dale can’t prove it yet, but he thinks the design came from a collaboration between Aladdin and a well-known architect who built large Arts & Crafts houses in Saginaw, 10 miles away.” And not a half mile from this house is one said to be modeled on the home of English architect C.F.A. Voysey.

The house remains true to the original plans. “It just needed some color to make it ours,” Todd says. “Previous owners had been very kind to the house, and that was our intention, too.” Though Todd and Ann had to tackle typical mechanical updates, they were spared from stripping white paint off the original art tiles on the fireplace in the den; the last owners had already done that. “But they left the white marble oddly added over the firebox,” Todd says. He created the more sympathetic mantel and wood trim, and added the vintage copper hood that he found in a Detroit shop.

Todd also renovated third-floor rooms, turning attic space behind the dormers into a home office on one side—“Arts & Crafts Industrial,” he calls it—and an Art Deco-inspired playroom on the other. He replaced the rotting front entry door with one he crafted around a beautiful panel of Prairie-style art glass from a Milwaukee house, using all the original hardware.

In collecting furniture and decorative objects, the couple lean toward work made in the Midwest: by Wheatley, Jarvie, and so on. They prefer Michigan-made items from Pewabic, Stickley Brothers, Limbert, and Lifetime Furniture. “I’d buy Gustav Stickley and Dirk Van Erp if given the chance,” Todd says, “but their pieces sometimes feel out of place here. I like local!” In the dining room, a sideboard with strap hinges is by Lifetime; the other is by Ohio’s King Furniture. One little lamp table under the triptych in the living room is early Gustav, ca. 1902. The heavy Morris chair next to it is from the Come-Packt Furniture Co. of Ann Arbor and Toledo.

Furnishing an Original

Filling the house with furniture of the same period—furniture made in the Midwest—created an interior that looks as it might have when the house was built. Almost everything is period, even the textiles, collected for years. Many things were inexpensive at the time of purchase. The big turquoise vase by Pewabic came from a resale shop. The art glass center panel hanging in the window of the stair hall, a mix of Prairie and Art Nouveau influences, was found in a restaurant that was closing in northern Michigan. They paid $20 at a yard sale for the large ceiling fixture in the dining room!

Mail-Order Kit Houses: Aladdin Homes

The Rossley is an unusual, higher-priced model that appeared in Aladdin’s 1916 catalog. Founded by the Sovereign brothers, who began with boathouses, garages, and summer cottages in 1906, Aladdin Homes were sold worldwide by the North American Construction Company of Bay City, Michigan. The family firm continued to manufacture kit houses until 1981, though it never fully recovered after the Depression. (The rights to the company name and logo were recently acquired by a third party.)

Unlike earlier mail-order plans companies, Aladdin was the first of seven major firms that sold affordable, pre-cut kits that could be assembled by several carpenters—or even a homeowner and friends. Between 1910 and 1940, Aladdin offered more than 450 different models. The attractive catalogs helped create interest in Craftsman, bungalow, American Foursquare, and Cape Cod styles for houses.

Success came from multiple sales for “company towns.” Hopewell, Virginia, for example, was developed by the DuPont Company using Aladdin kit homes. By 1916, the Aladdin catalog was a hundred pages and in color. By then the kits included indoor bathrooms in many models, along with built-in clothes closets. Though the houses were sold with unfinished kitchens, cabinets and Hoosiers were available as add-ons, as were bath fixtures and even suites of lighting fixtures.

Patricia Poore is Editor-in-chief of Old House Journal and Arts & Crafts Homes, as well as editorial director at Active Interest Media’s Home Group, overseeing New Old House, Traditional Building, and special-interest publications.

Poore joined Old House Journal when it was a Brooklyn-brownstoner newsletter in the late 1970s. She became owner and publisher and, except for the years 2002–2013, has been its editor. Poore founded the magazines Old-House Interiors (1995–2013) and Early Homes (2004–2017); their content is now available online and folded into Old-House Journal’s wider coverage. Poore also created GARBAGE magazine (1989–1994), the first unaffiliated environmental consumer magazine.

Poore has participated, hands-on, in several restorations, including her own homes: a 1911 brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and a 1904 Tudor–Shingle Style house in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she brought up her boys and their wonderful dogs.